Recently, Barbie caused quite a stir when she posed (rather, was posed) for the cover of Sports Illustrated. In a feature article, she “speaks” about her experiences, claiming,

“I, for one, am honored to join the legendary swimsuit models. The word “model,” like the word “Barbie®,” is often dismissed as a poseable plaything with nothing to say. And yet, those featured are women who have broken barriers, established empires, built brands, branched out into careers as varied as authors, entrepreneurs and philanthropists. They are all great examples of confident and competent women.”

Those are mighty words for a doll. Barbie makes sure to place the “registered trademark” image next to her name as she goes on to utilize hashtags in telling women not to apologize for controlling empires. What’s wrong with this picture? Like the women who shaped her, Barbie lacks an understanding of class as it operates globally and locally. Having women in positions of corporate leadership is not the same as advancing gender equality worldwide. Atop her throne of capitalist consumerism, Barbie believes that women and girls are really only discriminated against for being too girly, too pretty, or loving fashion too much. Her advice? “Be free to launch a career in a swimsuit, lead a company while gorgeous, or wear pink to an interview at MIT.” In saying so, Barbie forces girls and women into the boxes she speaks so strongly against.

I don’t think that anyone has ever “dismissed” anything that Barbie has said or done. Rather, I am hyperaware of the ways in which her plastic persona both directly and indirectly conveys messages about normative female social roles to those who purchase and play with her. And I’m not the only one. Earlier this week, the Guardian conducted a study of young girls who played with Barbies, and found that “After only five minutes of playing with Barbie, girls in our sample said that boys could do more jobs in the future than they could. Girls who played with Mrs. Potato Head, on the other hand, responded that they could do about the same number of jobs as boys someday.” According to the study, Barbie further socializes girls to believe that they can only occupy limited, gendered roles.

When Teen Talk Barbie debuted in 1992, the first words out of her mouth were, “Math class is tough!” The first ever talking Barbie, a doll who had for years prided herself on the motto “We girls can do anything,” chooses to complain about math? Yes, math is tough. But rather than construct a narrative about doing homework, working hard, or actually doing math, Barbie discourages girls from pursuing it.

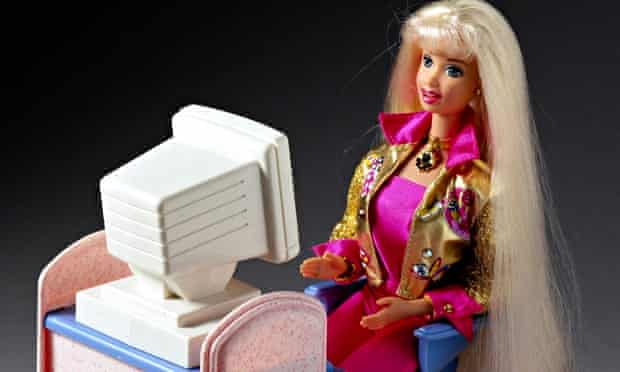

Perhaps this is why it wasn’t until 2010 that Barbie became a computer engineer. The doll, designed in collaboration with the Society of Women Engineers, wears neon pink glasses, a neon pink Bluetooth headset, a neon pink watch, and carries a neon pink smartphone and a neon pink computer. Her shirt, in neon green, pink, and blue, has a picture of a computer and some binary code, illustrating that even when Barbie branches out into STEM fields, she is still bound to ridiculous, gendered constraints. In an effort to incorporate as much pink as possible into her wardrobe, Barbie must literally wear the image of a computer on her shirt to convey that she is a computer engineer.

While the AAUW lauds the creation of this doll, quantitative representations in STEM fields are not enough. I want to see a world in which Barbie not only represents different career possibilities, but represents them accurately. Mattel cannot overlook the problems of its past by continuing to send mixed messages in the future. Today’s Barbie adopts the slogan “Be who you wanna be!” What she really says, is ‘Be who you wanna be, as long as you’re considered to be conventionally attractive, you wear lots of pink, and are committed to amassing a fortune with a multimedia empire.” And frankly, that’s just not good enough.

(Photo Credit: SSPL / Getty Images / The Guardian)