(Image Credit: BASFLonmin)

women in and beyond the global

analyzing and changing the status of women in households, prisons and cities

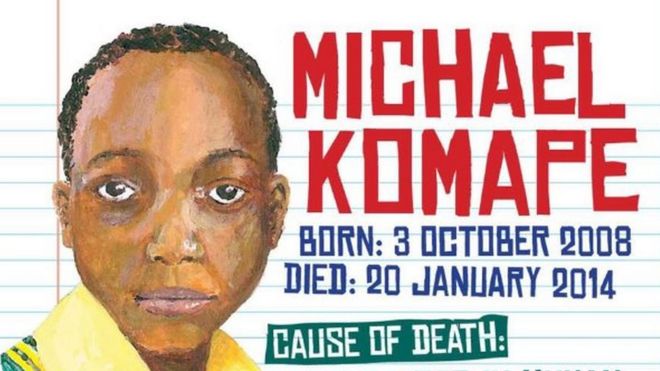

On January 20, 2014, Michael Komape, five years old, went to the toilet in his primary school in Limpopo, in South Africa. He never returned. The toilet seat was corroded, gave way, and Michael Komape fell into the pit and drowned to death in feces. Three years later, his parents and siblings have received neither apology nor support from anyone in government. His parents sued the Minister of Basic Education, and that trial began last week. Today, the court heard that the Department of Basic Education had been warned numerous times about the dangerous condition of toilets in Limpopo schools. The Department did nothing. The Department received three series of warning letters, in 2004 and 2008 and 2009, that described the school’s toilets as dangerously sinking. The State did nothing. Doing nothing means refused to act. Michael Komape did not fall to his death in a pit latrine. He was pushed, by a State that decided it had more important issues to deal with. In 2014, five-year-old Michael Komape did not fall to his death. He was murdered.

The afternoon of January 20, 2014, the school called Michael’s mother, Rosina Komape, to tell her that Michael was “missing.” Rosina Komape went to the school, and a classmate of Michael’s told her that Michael had last been seen going to the toilet, an outside pit latrine. School officials denied this, and claimed that Michael had gone out to play. Rosina Komape told the classmate to take her to the toilets: “When I looked inside the toilet I saw Michael’s hand. I then said that my child died asking for help … I asked them to pull him out by the hand maybe we can save him. I thought if we pulled him out we could save him. The principal said they had called someone to pull him out. I thought he was still alive and if we pulled him out and took him to hospital he would get help.” Michael Komape drowned in a pool of human feces, reaching to the sky. His mother came and found his outstretched arm.

The family is traumatized by and angry with the State. Days of testimony have revealed what we already knew, that the family of parents and siblings is grieving and living with nightmares, that the State has steadfastly stood fast and never extended any kind of hand to the family, and that this was a death foretold. In South Africa, 4624 schools have pit latrines.

The family is haunted, but not the State. Why not? While this story is particular to South Africa where it is seen as yet another referendum on the state of the democracy, and the human heart, it sits with similar stories around the world. It’s the story of neoliberal development, centered on global cities. Walk the streets of the Cape Town or Johannesburg or Washington, DC, metropolitan centers, and you will see extraordinary change taking place. Buildings go up, streets are torn up to lay underground cables, mansions rise where once modest homes sat, shopping malls and boutique shops proliferate, and the list goes on. Who pays for that? Michael Komape, Michael Komape’s brothers and sisters, Michael Komape’s mother and father. Last Wednesday, James Komape, Michael’s father, said, “They should have helped. My son was going to school. I did not send him to die.” I did not send him to die, and yet he was sent to his death, by a State that prefers waterfront malls to safe and secure school toilets.

Someone once wrote “Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear … twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.” Today, the first time is tragedy, and the second horror. Michael Komape did not fall, and his death, however painful and haunting, was not tragedy. Michael Komape was murdered, and, other than the family, who today is haunted? Who is haunted by the dead of Marikana, by the dead of Life Esidimeni, by the dead five-year-old child drowning in a pool of shit, reaching to the sky? When we look, do we see Michael’s hand? We should have helped.

Michael Komape two months before he died

“This silence calls out unconditionally; it keeps watch on that which is not, on that which is not yet, and on the chance of still remembering some faithful day.”

Jacques Derrida, “Racism’s Last Word”

August 16, 2017, marked the fifth anniversary of the massacre of Marikana, in which 34 protesting miners were killed by the police, in the single most lethal use of force by South African security forces since the March 21, 1960 Sharpeville massacre, when security forces killed 69 people. August 16 2017, people gathered in Charlottesville, and around the world, for the memorial service for Heather Heyer, murdered by a white supremacist in Charlottesville, Virginia, Saturday, August 12. Both commemorative and memorial events were marked, in social and news media, with injunctions to never forget and to always remember. We will not forget you. #RememberMarikana #RememberHeatherHeyer #NeverForget. Will we remember Marikana? Will we remember Heather Heyer?

We may have a trace of memory within, but that is not remembering. If we remembered, meaning if we held the moment or the event or the person(s) present in their absence, five years would not have passed as they have, and, five years from now, who will `remember’ Heather Heyer? I don’t mean that last question as a condemnation, but rather something to study and engage with, as those memories and remembrances will engage with us … or not.

34 miners were killed by bullets on a hill in South Africa. Their names are Tembelakhe Mati, Hendrick Tsietsi Monene, Sello Lepaaku, Hassan Fundi, Frans Mabelane, Thapelo Eric Mabebe, Semi Jokanisi, Phumzile Sokanyile, Isaiah Twala, Julius Langa, Molefi Ntsoele, Modisaotsile van Wyk Sagalala, Nkosiyabo Xalabile, Babalo Mtshazi, John Kutlwano Ledingoane, Bongani Cebisile, Yawa Mongezeleli Ntenetya, Henry Mvuyisi Pato, Ntandazo Nokamba, Bongani Mdze, Bonginkosi Yona, Makhosandile Mkhonjwa, Stelega Gadlela, Telang Mohai, Janeveke Raphael Liau, Fezile Saphendu, Anele Mdizeni, Mzukisi Sompeta, Thabiso Johannes Thelejane, Mphangeli Thukuza, Thobile Mpumza, Mgcineni Noki, Thobisile Zimbambele, Thabiso Mosebetsane, Andries Motlapula Ntsenyeho, Patrick Akhona Jijase, Michael Ngweyi, Julius Tokoti Mancotywa, Jackson Lehupa, Khanare Monesa, Mpumzeni Ngxande, Thembinkosi Gwelani, Dumisani Mthinti and Mafolisi Mabiya. Heather Heyer was killed by a car in the streets of the United States.

Today is Friday, August 26, 2017. Who today spoke the names of these 35 martyrs? Who stopped what they were doing, today, and “remembered”. Who re-membered them, who re-called them, who conjured them … today?

In November 1983, an exhibit entitled “Art contre/against Apartheid” opened in Paris. Jacques Derrida contributed an essay, “Racism’s Last Word” to the catalogue. Derrida hoped that Apartheid would be the name “for the ultimate racism in the world, the last of many.” He saw the purpose of the exhibition as creating a memory of the future: “A memory in advance: that, perhaps, is the time given for this exhibition. At once urgent and untimely, it exposes itself and takes a chance with time, it wagers and affirms beyond the wager. Without counting on any present moment, it offers only a foresight in painting, very close to silence, and the rearview vision of a future for which apartheid will be the name of something finally abolished. Confined and abandoned then to this silence of memory, the name will resonate all by itself, reduced to the state of a term in disuse. The thing it names today will no longer be. But hasn’t apartheid always been the archival record of the unnameable? The exhibition, therefore, is not a presentation. Nothing is delivered here in the present, nothing that would be presentable-only, in tomorrow’s rearview mirror, the late, ultimate racism, the last of many.”

The unnameable showed up on that hill in 2012 as it did in the streets of Charlottesville in 2017. The late, ultimate racism, the last of many, has not yet ended; it is alive and killing, taking lives, threatening entire populations. When we speak the names of the martyrs, we speak their names in a raging ocean of unconditional silence, the silence of the massacred, and we cannot yet claim to remember them. That faithful day has not yet come, and we are not yet at racism’s last word. Instead of promising to remember and to never forget, let us try as best we can to speak the names in the hope that someone might hear, might understand, and might, might, just carry it on.

(Speaking Wounds: Voices of Marikana Widows Through Art and Narrative)

(Image Credit: The Journalist)

(Photo Credit: Greg Nicolson / Daily Maverick)

SIKHALA SONKE: The Women of Marikana invite you to bear witness to their lives in Marikana in August 2014

Re: site inspection and speak out by the women of Marikana, 12 August 2014

| WHAT? A site inspection of Wonderkop, Marikana followed by a brief speak-out in which the women of Marikana and widows will testify to their ongoing pain and experience of injustice. They will talk about what they want to change in their lives.WHO? Ministers and Parliamentarians, the Office of the Premier in the North-West province, representatives of Chapter Nine bodies, prominent civil society leaders and cultural workers.

WHEN? Tuesday 12 August at 11am outside the main entrance to the Wonderkop Stadium. |

Nearly two years has passed since the massacre of striking mineworkers in Marikana on 16 August 2012. Media and public attention has since been focused on the Farlam Commission and, more recently, on the five-month plus strike action on the Platinum belt. Eyes have long been turned away from day-to-day life in Marikana, and the distant rural villages and towns from which some of the mineworkers, killed in the massacre, originate and where their surviving families remain.

As we approach the two year anniversary of the Marikana massacre, it is an appropriate time to ask:

– Are the Lonmin workers and community members living in conditions any better than two years ago? What has Lonmin done to improve lives? What has the local municipality done?

– What justice has there been for the widows of Marikana and the families of the mineworkers that were killed? Has there been any compensation for their grievous losses? How are these families being supported by Lonmin and government?

– Do workers and the community feel that justice has been served in the past two years?

The women of Marikana – organised as Sikhala Sonke – invite you to bear witness to their living conditions, their continued suffering and their acute feeling that justice for workers, for widows, for the community as a whole has not been served.

Please RSVP or send your queries to sikhalasonkejustice@gmail.com. You may also phone ThumekaMagwangqana on 084 714 0111.

We look forward to meet you on the 12th August in Marikana,

Sikhala Sonke

SIKHALA SONKE: The Women of Marikana

Site Inspection and Speak Out, 12 August 2014

Programme

10:30am Gather at tent erected close to the Wonderkop Stadium, Nkaneng, Marikana

11:00am Welcome, why we are here and outline of programme for the day (Sikhala Sonke)

Bishop Jo Seoka – opening words and prayer

11:15am Depart for site inspection (Sikhala Sonke)

12:15pm Conclude site inspection at assembly point

Testimonies from women and widows of Marikana

Remembering Paulina Masuhlo (Sikhala Sonke and family of Paulina Masuhlo)

Reading of Sikhala Sonke letters to government

1:00pm Responses from invited guests and other organisations gathered in solidarity

Reading messages of solidarity

1:50pm Closing words and prayer – Bishop Paul Verryn

Refreshments and departure

(Photo Credit: Sikhala Sonke – Mama Marikana)

South Africa is currently awash in commissions of inquiry. There’s the ongoing and perhaps never-ending Marikana Commission. Today we read there’s to be a new commission of inquiry into the Tongaat mall collapse, last November. And there’s the Khayelitsha Commission of Inquiry into allegations of police inefficiency in Khayelitsha and a breakdown in relations between the community and police in Khayelitsha.

While women are significant participants in the Marikana and the Tongaat events and commissions, women are in many ways the subjects of the Khayelitsha Commission. This is not surprising, given the nature of the inquiry. The Commission’s mandate isn’t to get to the bottom of a tragic event, but rather to investigate and get to the texture of decades long dissolution of everyday life.

In the 1980s, the State built Khayelitsha and has continued to do so ever since. Part of this construction has involved the establishment of a State of sexual tyranny. That State of sexual tyranny has come forth in the testimony of Khayelitsha residents to the Commission.

The Commission began in response to a complaint lodged by the Women’s Legal Centre, representing the Social Justice Coalition, Treatment Action Campaign, Equal Education, Free Gender, Triangle Project, and Ndifuna Ukwazi. That complaint was lodged in 2012. The Social Justice Coalition had been organizing hard for two years prior for an investigation into the situation of justice administration in Khayelitsha. As the complaint noted, “Since 2003 the civil society organisations have held more than one hundred demonstrations, pickets, marches and other forms of protest against the continued failures of the Khayelitsha police and greater criminal justice system. The organisations have also submitted numerous petitions and memorandums to various levels of government in this regard. There have been sustained and coordinated efforts from various sectors of the Khayelitsha community for action to be taken by government agencies, including the police, to improve the situation.”

For over a decade, intensifying police incompetence, corruption, violence, and disregard for the local population went hand in hand with `vigilante justice’. In 2012 alone, 20 `vigilante’ collective killings were reported in the area. The struggle for space and for citizenship was running with blood and smoke. In the struggle for safe space and full citizenship, women, again, have been key. As the Women’s Legal Centre complaint noted, “Girls and women are frequently beaten and raped whilst walking to and from communal toilets or fetching water from communal taps close to their homes, while domestic abuse poses a threat to the safety of many women within their own homes. Between March 2003 and March 2011 there has been a 9.36% increase in the number of reported sexual crimes reported in Khayelitsha.”

Throughout the decades, women have kept their eyes on the prize. Khayelitsha is home. They should be able to live, and love, at home without fear of violence. Their children, partners, parents, friends, neighbors should as well. Through the use of public funds and private security forces, Cape Town has established `improvement districts’ … in the central city, inner southern suburbs, Sea Point and Green Point. Not in Khayelitsha. The women know that, and they don’t accept it.

Funeka Soldaat, founder of Free Gender, recounted her story of being raped, because she is lesbian, in 1995. She went to one police station, where nothing happened. Finally, without her statement being taken, she was taken to a hospital and dumped outside. The hospital said she needed a statement, and so she walked to Khayelitsha Site B police station, all of this right after having been raped. There she was treated disrespectfully, she felt because of her sexual orientation, and no statement was taken. Finally, literally barefoot, she walked home and went to sleep. The rest of the story is pain, healing, organizing. As to the police: “Khayelitsha police appear to lack the energy, will and intent to provide a service to LGBT [people].”

Malwande Msongelwa described what happened when she found her brother, stabbed to death at a bus stop. She called the police, and they didn’t come. She called again, and they finally came, but did nothing. Worse, they refused to get out of their cars: “The police do not care about people… [they] will only come out if there are drugs. Then they will come out with 10 cars …They do not even care if you are injured… If the ambulance hasn’t arrived they won’t touch you. They wait in their car… I don’t trust the police.” Her brother lay on the ground for six hours. The crime scene was never investigated.

The stories continue. Ms. Nduna describes how a police van hit and dragged one of her children. This was the fifth child in the area to suffer harm, and worse, at the hands of a police vehicle. What happened? “We buried and there was nothing still.”

The harrowing stories of violence, of police inaction and worse, of vigilante action and worse, occur in a framework of radical hope. Phumeza Mlungwana, Secretary General of the Social Justice Coalition, put it simply and directly: “Most of Khayelitsha is policeable.”

Witness and after witness explained that lights, presence, a diversity of site appropriate techniques, a committed and engaged and respectful police force are what are called for. It’s not rocket science, and it’s not impossible. The women of Khayelitsha know that. They know, from experience, that when the work of struggle accompanies the work of mourning, they can make things happen. The Commission itself is a step along that path. The struggle continues.

(Photo Credit: Kate Stegeman / Daily Maverick)

It’s been a year, almost, since the massacre at Marikana, and the nation, and its media, are struggling, sort of, to find a way to address all that has, and even more has not, happened in the intervening year. A year later, tensions simmer, the Farlam Commission is more or less falling apart, some great and moving documentaries are beginning to emerge, and the widows of Marikana organize and wait, wait and organize.

This is how the week began. On Sunday, in a prayer service in Langa, national police commissioner Riah Phiyega announced that South Africa would `commemorate’ the Marikana tragedy. How exactly will the police, who used live ammunition to put down a mineworkers’ strike, `commemorate’ the event?

More to the point, is commemoration the best way to honor the dead miners and, even more, their survivors, the widows and children? As one widow explained, soon after the massacre, “Today I am called a widow and my children are called fatherless because of the police. I blame the mine, the police and the government because they are the ones who control the country.”

How will `the nation’ commemorate those who are now called widows and those who are now called fatherless? What happened on August 16, 2012? 34 miners were killed. Many others were wounded. And widows were made. Soon after one mineworker was arrested, police told him, “Right here we have made many widows … we have killed all these men.”

The State machinery, call it a factory, produced widows of women that day, and has continued to produce widows of those very women every single day since. So, here’s a suggestion. Rather than `commemorate’, compensate.

(Photo Credit: Greg Marinovich /Daily Maverick)

The names. The names of places: Armadale, Marikana. The names of sectors: the garment industry. The names of those individuals whose names cannot be shared: Laura S. The names of the men: Jimmy Mubenga. The names of the women: Ishrat Jahan, Jackie Nanyonjo, Savita Halappanavar. The names of the children: Ashley Smith, Trayvon Martin.

These are but some of the names of the innocents, slaughtered by State policy and practice. These are but some of the people we have tried to describe over the last little time. These are the names of those whose tragedies have opened too many doors to the work of mourning.

We have written, others have written, to what end?

“To write, to him – present to the dead friend within oneself the gift of his innocence. For him, I would have wanted to avoid, and thus spare him, the double wound of speaking of him, here and now, as one speaks of one of the living or one of the dead. In both cases, I disfigure, I wound, I put to sleep, or I kill. But whom? Him? No. Him in me? In us? In you? But what does this mean? That we remain among ourselves? This is true but still a bit too simple.”

After the silence, after the too-simple truths, what is there? If we are to present to the dead friends within oneself the gifts of their innocence, we must earn the gift. We must organize the State of peace, justice, mutuality, love. All else is … words.

And Trayvon Martin is dead.

(Photo Credit: Livemint.com/Gauri Gill)

Copyright © 2024 · Magazine Child Theme on Genesis Framework · WordPress · Log in