Lebanon 2023

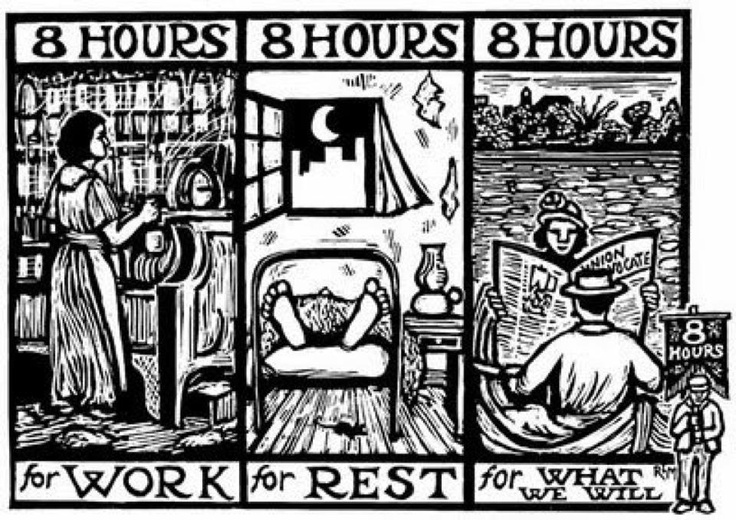

“Yesterday was May 1, 2011. Around the globe, millions marched. Among the workers marching were sex workers, domestic workers, other denizens of the informal economy. Today is May 2, 2011. What are those workers today? Are they considered, simply, workers or are they `workers’, part worker, part … casual, part … informal, part …shadow, part … contingent, part … guest? All woman, all precarious, all the time.” Today is May 1, 2023. What will tomorrow bring for sex workers, domestic workers, care workers, and other denizens of the informal economy? Twelve years later, after so much organizing, where exactly, and who exactly, are we?

Much has happened over the past twelve years, and much has remained the same. Nation-states have recognized domestic workers as formal, or actual, workers. On June 16, 2011, the ILO ratified the ILO Convention Concerning Decent Work for Domestic Workers, which came into force on September 5, 2013. In 2013, the ILO estimated the Convention could affect the lives of 53 million domestic workers, not including child domestic workers. At that time, the ILO estimated there were 10.5 million children working as domestic workers. Those numbers have only grown in the interim. At last count, 39 countries have ratified ILO Convention 189. Many more have not, including France, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Spain ratified this year.

Recently, The Monitor, in Uganda, has been running a series entitled “Maid in Middle East”, focusing on individual stories of Ugandan workers difficult lives, and often tortured deaths, as workers in various countries across the Middle East. From 2016 to 2021, approximately 24,100 Ugandans, mostly women, went each year to work in the Middle East. In 2022, that number was just shy of 85,000. Meanwhile, today, according to The Monitor, seven out of ten employed Ugandans work without a contract or any job security. As Filbert Baguma, General Secretary of Uganda National Teachers’ Union, UNATU, today noted, “We don’t have what to celebrate because workers continue to be marginalised as their employers pretend to be paying them. If you pay me whatever you want and you continue to use words like, you can take it or leave it and go, be patient, up to when?’’ Up to when? Uganda has not ratified ILO Convention 189.

Across the world, workers and allies have protested various forms of abuse, exploitation, and violence. Domestic workers have figured prominently in some of those demonstrations, in others, not so much. In Hong Kong, 340,000 so-called migrant domestic workers have faced abuse and exploitation “for decades”. For decades, domestic workers in Hong Kong have taken to the streets, courts and embassies to demand and seize dignity, respect, autonomy, recognition and power. Women like Nancy Almorin Lubiano, Erwiana Sulistyaningsih, Evangeline Banao Vallejos, and so many others went to court to challenge both employer and State physical, emotional, psychological and structural violence. During that same period, Baby Jane Allas, Milagros Tecson Comilang, Desiree Rante Luis suffered terrible abuse at the hands of employers and State, while, like so many other migrant domestic workers, Sophia Rhianne Dulluog died “under mysterious circumstances.” China has not signed ILO Convention 189.

In 2015, domestic workers in Lebanon organized a union. Today, with supporters and in the midst of national economic and social crisis, they marched through the streets of Beirut, demanding an end to violence against domestic workers. As did their sisters in Bangladesh and Jamaica, along with calling out the violence itself, they noted that many of the so-called protections exist on paper only. There is less than no enforcement; violators and predators are effectively encouraged to go on about their business undisturbed. Lebanon and Bangladesh have not ratified ILO Convention 189; Jamaica has.

For the past twenty years, in the larger DC – Maryland – Virginia metropolitan region, a group of Latin American immigrant women who fled their homes and homelands to escape violence. They are Madre Tierra, Mother Earth, and they have connected around 500 people seeking asylum or legal status with attorneys. They have provided support and community to survivors of domestic violence, sexual assault, human trafficking, forced marriages, and persecution for their sexual identities. The group itself numbers around 80. Many, if not most, work as house or office cleaners, at exploitatively low pay. The members realized that for them to address the violence, they had to build power, and that included economic and worker power. And so, they are forming a cleaners’ cooperative, Magic Broom. Magic Broom currently has 12 members. Jean Carla Paloma, originally from Bolivia, explained, “This will allow us to come together and make a living and hopefully get the means to be able to sustain ourselves … [It will] teach women about their rights so they can know when they’re being discriminated against and how to prevent violence.” Consuelo Barboso, originally from Colombia, agreed, adding, “Unification is what brings us power.”

From massive marches to cooperatives of 12, unification is what brings us power. Unification is a process, not a single place nor a single day. Unification means mutual recognition in the formation and sustenance of solidarity. Unification itself is work, as are mutual recognition and solidarity. Unification brings us power; call them, simply, workers.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Photo Credit: Bilal Hussein / AP / HJ News)