Kindra Chapman

On Monday, July 13, #BlackLivesMatter activist and outspoken critic of police brutality Sandra Bland was “found” dead in a Texas jail. On Tuesday, July 14, in Homewood, Alabama, 18-year-old Black teenager Kindra Chapman was arrested, at 6:22 pm. At 7:50 pm, Kindra Chapman was found dead, hanging by a bed sheet in a holding cell.

While the case of Sandra Bland has attracted extensive and intensive attention, with one or two exceptions, the death of Kindra Chapman has not.

Suicide in jails and prisons, and in particular women’s jails and prisons, is the new normal, and not only in the United States. For example, just yesterday, it was reported that, in the United Kingdom, the number of people dying in police custody has reached its highest level for five years. We reported on this earlier in the year. The story’s the same in Italy.

Meanwhile, the jails of America are filling up to choking as the prisons are “releasing”, and women, and especially Black women, have been the principle actors, and targets, of this new phase of mass incarceration. And then there are the immigration detention centers. At Women In and Beyond the Global, we have been covering this trend for years. Here are just some of the individual women’s stories we’ve followed.

In 2007, in a Canadian prison, after years of mental health torment and begging for help through self-harm, 19-year-old Ashley Smith killed herself, on suicide watch, while seven guards followed orders, watched and did nothing. Now Ashley Smith haunts the Canadian Correctional Services … or doesn’t.

In 2013, in England, Ms. K died. Her death was exemplary. A woman enters prison for the first time, a troublesome woman, and within weeks is found hanging in her cell. For the Ombudsman researchers, Ms K’s case is “one example” of the “failure” to “consider enhanced case review process” when a prisoner’s history suggests “wide ranging and deep seated problems.”

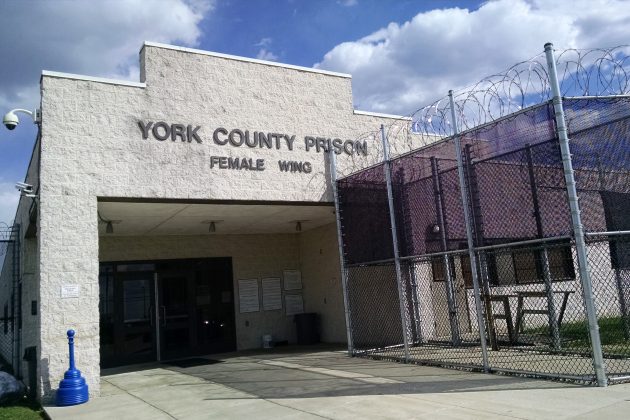

Last year, on Thursday, September 18, Megan Fritz hung herself. On Monday, September 22, Mary Knight did the same. Both women were incarcerated at Pennsylvania’s York County Prison when they committed suicide. Yet neither woman was on suicide watch. Why not?

Josefa Rauluni left the island nation of Fiji for Australia, where he applied for asylum, or “protection”. He was turned down. He was taken to Villawood Detention Centre, run by Serco. He continually appealed the decision, saying he feared for his life if he returned to Fiji. In response, the State told Josefa Rauluni that he would be deported on September 20, 2010. The night of September 19, Josefa Raulini sent two faxes to the Ministerial Intervention Unit at the Department of Immigration and Citizenship. They read, ”If you want to send me to Fiji, then send my dead body”. The State did nothing. On the morning of September 20, 2010, Josefa Raulini informed the guards, “I’m not going, if anyone goes near me, I will jump“. The guards did nothing for a while, and they they tried force. As they moved in, Josefa Raulini jumped from a first floor balcony railing. He dove, head first, hit the ground, and died. The State did nothing; the Villawood staff had no suicide prevention training.

On December 20th 2013 Lucia Vega Jimenez committed suicide, hanging herself in a shower stall of a bleak border facility at the Vancouver International Airport under the jurisdiction of Canada Border Services Agency, CBSA. She died eight days later in a hospital. She somehow found a rope and hanged herself. Who brought the rope and who tied the knot?

Lilian Yamileth Oliva Bardales, 19 years old, and her four-year-old son had been held in Karnes “Family Detention Center” from October to June. She had applied for asylum, explaining that she had fled Honduras to escape an abusive ex-partner, six years older than she, who had beaten her regularly since she was 13. Her application was denied. In early June, she locked herself in a bathroom and cut her wrists. She was removed from the bathroom, held for four days under medical “supervision” during which she was denied access to her attorneys, and then deported.

The line from Sandra Bland to Kindra Chapman is direct, a line of Black Women killed in police custody. The coroner’s report may say they hanged themselves, and they may have, but if there’s an epidemic of self harm and suicide and the State does nothing, that’s public policy, and it’s murder. Likewise the line between Canadian Ashley Smith and English Ms. K and Mary Fritz and Mary Knight and Kindra Chapman is direct, as is the line that binds asylum seekers and immigration detention prisoners Josefa Rauluni, Lucia Vega Jimenez, and Lilian Yamileth Oliva Bardales. These women, and men, are captives in jails and prisons in which there is no suicide prevention training or planning. Quite the contrary, prisoner suicide is part of the plan. #IfIDieinPoliceCustody say my name. If she dies in police custody, #SayHerName.

(Photo Credit: al.com)