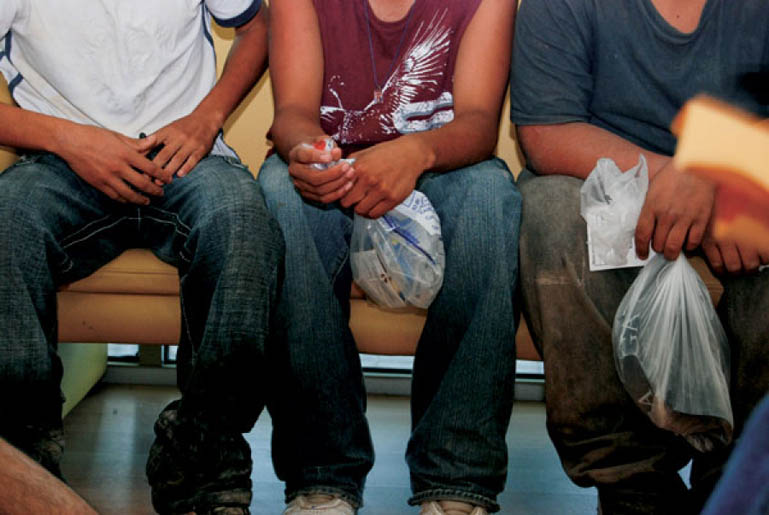

In July, ProPublica’s investigation of the conditions of immigrant youth shelters found a disturbing number of incidences of sexual abuse in multiple shelters around the United States. Within the past five years, police have responded to 125 calls reporting sex offences at shelters that solely serve immigrant children. Those numbers don’t include the additional 200 calls from more than a dozen shelters that care for at-risk youth. For children who are already facing obstacles, taking the dangerous trek crossing the border with or without their parents, the incidences of being abused by other residents and staff members is continuous traumatization. These children’s centers have received nearly $4.5 billion for housing and other services since the surge of unaccompanied minors from Central America in 2014. The high-profile incidents, where staff and residents have acted as predators, have led to arrests. One of the more heinous reports include a youth case worker who was convicted of molesting seven boys over nearly a year at an Arizona, having worked for months without a full background check.

Substantial changes to protect children or investigate incidences at the shelters have been slow to address the issues in the shelters, to the point of gross negligence.

Late last month, investigators warned that the Trump administration had waived FBI fingerprint background checks of staffers and had allowed dangerously few mental health counselors at a tent camp housing 2800 migrant children in Tornillo, Texas. More recent reports suggest that investigations into reports by migrant children are opened and closed, within alarming speeds. Often within days, or even worse, hours.

In one incident, a 13-year old named Alex was housed in Boystown, outside Miami. Alex was assaulted by other residents of the facility. After a few days of harassment by the perpetrators, Alex reported the assault to his counselor: “The counselor told him that a surveillance tape had captured the teenagers dragging him by his hands and feet into a room, and that there might have been a witness. But Alex’s report did not trigger a child sexual assault investigation, including a specialized interview designed to help children talk about what happened, as child abuse experts recommend. Instead, the shelter waited nearly a month to call the police. When it finally did, a police report shows, the shelter’s lead mental health counselor told the officers ‘the incident was settled, and no sexual crime occurred between the boys like first was thought among the staff.’ And instead of investigating the incident themselves, officers with the Miami-Dade Police Department took the counselor’s word for it and quickly closed the case, never interviewing Alex.”

A spokeswoman for the Archdiocese of Miami reported that it had handled the boy’s case correctly and blamed Alex for the delays. The Archdiocese has received $6 million in Miami just last year to care for 80 children at Boystown.

Many obstacles are put into place to stop children like Alex from speaking about their assaults. Children are intimidated by their attackers from coming forward, especially if that attacker is a staff member. Staffers at immigrant shelters report or conduct investigations, if at all, at a snail’s pace. Finally, many youth and their families fear reporting to the police, for fear of arrest and deportation.

Alex’s mother, Yojana, enraged that it had taken nearly three weeks to hear of the incident from staff, immediately wanted to go to the police and demand accountability from the shelter and the attackers, but her status as undocumented made her fearful of retaliation and arrest from ICE. As ICE agents have been arresting parents and family members, or members of their household when they come forward to claim their children — 170 sponsors or people connected to them have been arrested and 109 of those people had no prior criminal record — Yojana and her husband Jairo’s fear of being detained was legitimate. Alex feared his report would delay his release from the center.

Youth immigrant shelters have received large sums of money from the federal government to take care of children separated from their parents or detained because they came into the country as unaccompanied minors. When those children are hurt or abused while in those shelters, it is this country’s fault, the fault of the citizens who ignore and vilify those same children and their families. It is the non-profit’s fault for taking their money and not investing it in the care of children who are housed and waiting to go to their parents or guardians. The fault lies in the current administration and previous administration who caused the crises in Central America and now refuse to come to terms with the consequences of their actions in creating large populations of asylum seekers.

(Image Credit: ProPublica / Hokyoung Kim)