The Anju Project is an online community platform running in India and the global south; it is a place to connect with others, share stories of emotional abuse, and to find comfort for healing for people of marginalized genders who have experienced any form of abuse. Amruta Valiyaveetil imagined the need for such a platform out of her personal experience after an emotionally abusive relationship. She explains, “What broke me was not the relationship itself, but the fact that people around me didn’t believe what I was going through nor that my partner was capable of such actions.” She thought of The Anju Project as a platform for people whose natural support systems (family, friends, etc.) aren’t aware or ready to support others in emotional abuse situations. “What really helped me at that moment was reaching out to my partner’s ex-partners who were also abused by him, and I remember feeling very sane and supported in that process.” Hence, she began reaching out to more friends and family for support, which she says was much more meaningful than therapy.

Amruta combined her studies in Vet medicine, epidemiology with an emphasis on sexual and reproductive health and violence with her intersectional battle for gender rights and animal health.

She named the platform after her sister’s name “Anjana” which means “unknown” in Hindi. She remembers that Anjana was a special child and growing up she was always left behind; Anjana learned early what being marginalized meant and in time of need was always by Amruta’s side.

This platform is crucial in the current context of Covid 19 and its gender implication: “India has a deep patriarchal system that has affected and continues to affect everyone, not just women but also men and the LGBT+ community. It is in the daily mundane violence that you find yourself defeated bit by bit, and that plays out in intimate partner violence. Growing up in India, we constantly hear about anecdotes of extreme forms of violence, legitimized by society. The violence that comes before is unknown, misidentified, ignored, and/or not considered societally `enough’ to be violence. We should talk about subtle forms of violence. Emotional and psychological abuse need to be considered as violence; we must not merely wait for the physical abuse to categorize it as such.”

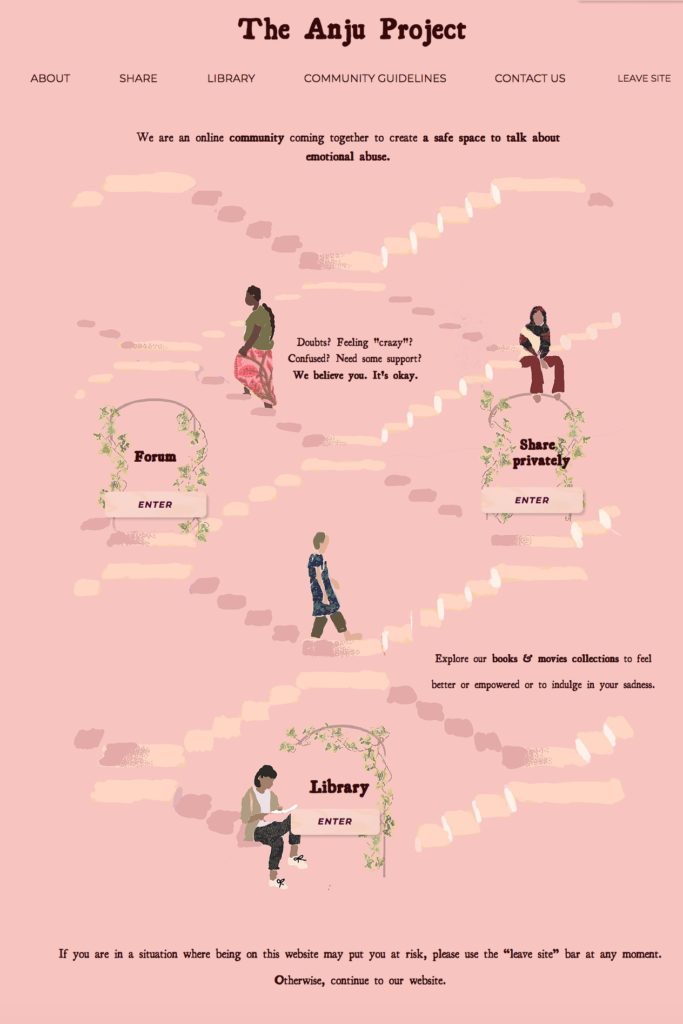

The Anju Project is a virtual, safe sharing space. “With everything moving towards digitalization, the Anju Project is an easy to access safe community to share stories of abuse. Everyone has the choice to share privately, to receive a personal response from an advocate, or to share on our community platform and receive responses from the community. In both cases, the interaction with the platform may remain anonymous or not. The posts are checked by our team members who are intimate partners violence advocates who also moderate the posts to guarantee the person’s safety and eliminate hate posts.” The Anju Project also has a curated library of books and movies with various themes ranging from health to art, with an overarching theme of understanding violence as a system that spreads throughout the world as a result of a variety of systems of domination.

The Anju Project is now searching for partnerships to spread the message across and expand its network. The Anju Project is currently partnered with Sakhi, an organization working against gender-based violence for South Asian women in the United States, and now, with Women Included, a transnational feminist organization. We strongly encourage initiatives and organizations working on the rights of marginalized genders and battling sexual and gender-based violence and intimate partner violence to connect with us. We also have a need for advocates and professionals who want to contribute their expertise to one-time events of their choice, as well as experienced digital social justice groups or personnel to support digitally.

Stay tuned for upcoming events on Instagram @theanjuproject or directly on the website TheAnjuProject.com:

- Art therapy Session: Expressing Emotion in Times of Turmoil

- Guided Creative Writing Session

- Online Weekly Support Groups

The creation of transnational feminist solidarity networks is crucial to transform society’s projections onto others’ differences, the differences that become cause for violence. As a member of both Women Included and The Anju Project, the interconnectedness driving the work we do became evident. It is nourished by our emotional and active engagement against all forms of domination and violence. We realize that violence is a devastating system connecting the entire Earth, and within that realization, we choose to emphasize and practice other systems that connect us – like compassion, innovation, togetherness, listening, art and voice – in our quest to eliminate violence against people.

by Mona Ayoub with Brigitte Marti