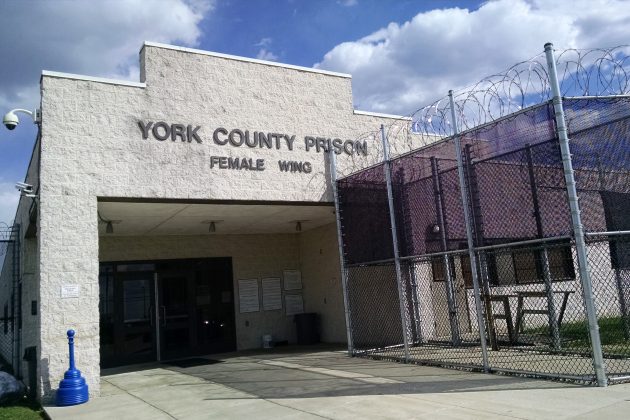

On Thursday, September 18, Megan Fritz hung herself. On Monday, September 22, Mary Knight did the same. Both women were incarcerated at Pennsylvania’s York County Prison when they committed suicide. Yet, as clearly indicated in nearly all of the media coverage of the incidents, neither woman was on suicide watch. Why weren’t Megan and Mary on suicide watch when they ended their lives?

One reason could be that what prisons and jails call “suicide watch” is an operating procedure disguised as a ‘prevention program’ implemented to protect facilities from liability. As the National Institute of Corrections notes, inmate suicides are financially, legally, and socially “devastating” for facilities and staff, often prompting lawsuits and negative publicity. Suicide watch is meant to care for prisons, not prisoners. Women behind bars are not ignorant– they are well aware of the negative consequences associated with suicide watch.

First, suicide watch leads to stigmatization for inmates, especially women. When women exhibit suicidal behavior or intention, they are often understood as ‘attention-seeking’ or ‘manipulative.’[1] Thus, suicidal women especially risk being labeled, distrusted, and disregarded. One correctional worker admitted that, “too often we conclude that the inmate is simply attempting to manipulat[e] their environment and, therefore, such behavior should be ignored and not reinforced through intervention.” One instructor of the Suicide Prevention training for correctional employees in Washington, D.C. taught his students that most suicide attempts are simply ways to “seek attention or misbehave.”

Pervasive attitudes like these lead to the poor treatment of inmates and impede care for those who need it.

In Northern Ireland, for example, female inmates at the Mourne House Unit and Maghaberry Prison reported[2] that it was normal for prison staff to bully suicidal women and those who self harmed. Correctional officers were known to taunt and laugh at women on suicide watch, blowing smoke in their faces and calling them names. When one woman felt she was in crisis, she called to ask for help, but the guard replied: “stop ringing the bell and shut the fuck up.” Another woman tried to hang herself twice in one day, yet inmates overheard a senior officer telling a subordinate officer, “don’t be looking in at her. Don’t even look at her. Fuck her.” Suicidal women are shamed, ignored, and persecuted when they express their feelings and needs.

Furthermore, when inmates admit to suicidal ideation or exhibit suicidal behavior like self-harm, they are often subject to harsher punishments as part of standard suicide prevention precautions. Those on suicide watch usually lose basic amenities like showers, bedding, phone calls, and family visits. They can be denied jobs and early release. Often, they are stripped of their clothing and are either left naked or are forced to wear “degrading and humiliating” paper safety smocks. National correctional standards require that they be housed in “suicide-resistant” cells; oftentimes, this means they are sent to solitary confinement or lockdown where they are isolated and deprived of sensory stimulation. In one county jail, suicidal inmates are confined in what they call “squirrel cages”: a 3x3x7 foot box fashioned out of chain-link fencing. Commonly, they are trapped there for more than 24 hours. Other correctional facilities utilize closed-circuit televisions to film suicidal inmates around the clock. Currently, the US Department of Justice is funding the evaluation of a device that “keep[s] track of inmates’ movements and vital signs using Doppler radar.” Being on suicide watch means losing what little freedom and autonomy inmates have. All of these ‘precautions,’ coupled with inappropriate responses from correctional staff, deter those in need from accessing mental health services, instead working as technologies of surveillance and control to further punish them.

Why didn’t Megan and Mary admit to feeling suicidal in York County Prison? Would you?

[1] Jaworski, Katrina. 2010. “The Gender-ing of Suicide.” Australian Feminist Studies 25(63):47-61.

[2] Scranton, Phil and Moore, Linda. 2005. “Degradation, Harm, and Survival in a Women’s Prison.” Social Policy & Society 5(1):67–78.

(Photo Credit: York County, PA, Government)