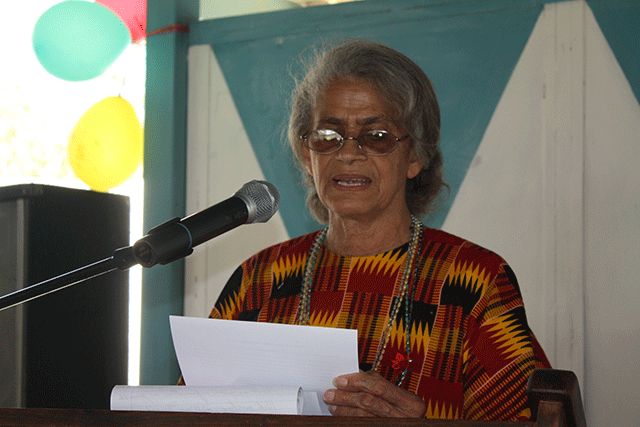

Ottilie Abrahams

On July 1, Namibian liberation activist, educator, feminist, movement builder Ottilie Abrahams died, at 80 years old. While many in Namibia, and in South Africa, mourned her passing, beyond the region little was made of her death or, more importantly, of her lifetime contributions. That’s too bad, because for those who care about justice, liberation, education, women and girls, and so much more, Ottilie Abrahams was, and is, a model.

Too full to summarize here, Ottilie Abrahams was one of the founders of SWAPO; one of the founders of the Yu Chi Chan Club, an armed revolutionary group; one of the founders of SWANLIF, South West African National Liberation Front; one of the founders of the Jakob Marengo Secondary School; one of the founders of the Namibian Women’s Association; and one of the founders of the Girl Child Project. That’s an abbreviated list.

Throughout her life, Ottilie Abrahams argued for the right to argue, think, contest, and demand. She mobilized women. She organized students and teachers. She criticized struggle comrades for their elitism and their corruption, and more than once was ‘invited’ to leave the organization and/or party. She welcomed every obstacle as an opportunity. The Jakob Marengo Secondary School is an example of that.

Ottilie and Kenneth Abrahams founded the Jakob Marengo Tutorial College in 1985. At that time, Namibia was still under the South African “mandate.” According to Kenneth Abrahams, the choice of name was “natural.” Jakob Marengo led the 1904 – 1907 War of Resistance to German colonialism. He was a national hero in a nation not yet recognized as such. Of equal importance, especially to Ottilie Abrahams, by 1985, Jakob Marengo was largely forgotten. She argued for the importance of historical memory. She researched Jakob Marengo’s life and she researched the popular archive of that life. Who remembered Jakob Marengo, and who did not? With that she designed a school committed to participatory democracy, critical thinking, and real and ongoing equality among both individuals and groups.

From her youth to her last day, Ottilie Abrahams worked ferociously to decolonize individuals and populations, to dismantle patriarchy, and to create a concrete transformative, liberatory, feministparticipatory democracy. In her writings and interviews, from beginning to end, the one constant is the insistence that democracy, if it is to be called democracy, must be participatory, and for that to happen, we all must engage in cointentional education. We must all be equally responsible for one another’s learning and wisdom. Ottilie Abrahams created a school in the image of the nation she believed Namibians, and everyone, deserves. Her school was based on “participatory democracy, critical thinking, non-sexism, responsibility and reciprocity as well as self-discipline.” As Ottilie Abrahams said, “These values are intended to produce people who will understand that they are their own liberators. Once they become adults, they will insist on participating actively in their own governance and become citizens who will work ceaselessly to make the world a better place for humanity as a whole.”

Ottilie Abrahams often said, “I will rest the day I die.” That day has come. Rest in peace Ottilie Abrahams. You provided the tools of critical feminist liberatory consciousness and action, which begins and ends with the recognition that liberation is within reach, and now, as always, the work of struggle continues.

(Photo Credit: The Namibian)