The aging of the largest generation in the United States, the Baby Boomers, is creating a desperate shortage for care workers for elders. By 2024, upstate New York will need 451,000 home health workers in 2024; currently the state employs 326,000. Already, the shortage is problematic for New York. For example, Rebecca Leahy of North Country Home Services reports that, every week, it is unable to provide a staggering 400 hours of homecare services which have been authorized by the state. Leahy explains, “My fear is that in the near future most patients in the three Adirondacks counties of Franklin, Essex, and Clinton could be without services because the sole provider for most of this region will not be able to cover payroll.” That would leave thousands of elders without the physical and emotional urgent care that they need.

The current trend, pushing us into a critical shortage of homecare workers, has been caused by the lack of well-paying jobs in the elder health-care industry. That lack creates a pool of continually underemployed workers. Upstate New York, and most of the country, consistently employs workers at wages and conditions that keep them in poverty, causing a high turnover rate of workers in a health industry that needs stability. Currently, the number of people in the United States over the age of 65 is expected to double. With the urgent and pervasive need for personal-care aids and home healthcare workers, employers and the state should provide jobs that give aids decent wages and benefits, including paid time off and health insurance.

Those benefits have not been procured by employees. Ai-jen Poo, Executive Director of the National Domestic Workers Alliance, has highlighted the extreme precariousness and vulnerability in elder care workers. With an industry where 90% of workers are women, the majority women of color and 30-40% immigrants, the conditions are impossible, ‘The average income for home care-workers is $17,000 a year. The median income for an elder care-worker…is $13,000.” Additionally, according to Poo, because they are characterized as domestic workers, elder care workers don’t qualify for work protections such as “limits on hours and overtime pay, days off, health benefits and paid leave.” Workers are completely dedicated to the patient who needs care, but are unable to receive the benefits and pay they deserve, many taking care of our families and loved ones.

Nearly 75% of nursing home care and home health care is paid for through Medicaid and Medicare, where the reimbursement rate has stagnated for several years. With the Trump administration’s attempts to roll back expansions granted under the Affordable Care Act, those reimbursements are unlikely to increase any time soon.

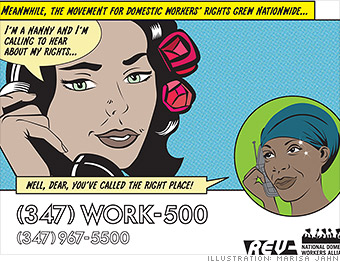

The National Domestic Workers Alliance is one of the leading organizations in the United States working for the inclusion of domestic workers, which include elder care employees, into the Fair Labor Standards Act which guarantees workers a federal minimum wage, overtime, sick, and vacation pay.

Caring Across Generations is a coalition of more than 100 local, state, and national organizations, working towards a policy agenda which includes, “access to quality care, affordable home care for families and individuals, and better care jobs.” The organization lists four major proposals to help address the underemployment of homecare workers and the growing need for elder care services:

- Increase the national minimum wage floor for domestic workers to $15.00 per hour.

- Improve workforce training and career mobility to ensure quality.

- Develop a path to citizenships for undocumented caregivers.

- Create a national initiative to incentivize and recruit family caregivers into the paid workforce, since nearly 85% of long term care is provided by family members.

According to Ai-jen Poo, domestic workers, including elder care workers, “need fair wages, decent working conditions and access to reproductive health care, including abortions”. It seems a simple request, considering these workers provide physical, mental and emotional care for our elderly family members while sacrificing their time with their own families. Given the emerging crisis, the time to help these workers is now!

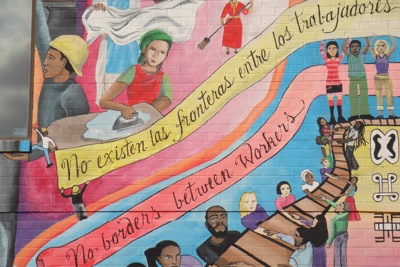

(Photo Credit: Caring Across Generations)