At the time of writing, nearly half the world has closed down or is waking up to an unfamiliar world of encroachments on physical mobility in ways not seen since the War of 1914 to 1918. Covid-19 has exposed existing fault lines in public health care provision and in public health crisis in both the global South and the global North. The realities of socioeconomic exclusion have exposed ongoing inertia in public service provision and the rescinding role of the State in those provisions. Race, gender and class have been foregrounded in this time of crisis. Whilst the Corona virus offers a critical moment to rethink and reframe the social compact between state, citizens and residents, it is also a dangerous and alarming time of enforced mass enclosure. This is not the first time that humanity has been here though the scale and reach are unprecedented.

Following Hurricane Katrina, many people sought to answer the question of whether its social effects and the government response to the country’s biggest natural disaster had more to do with race or with class. Media images broadcast from Louisiana showed nearly all those left behind to suffer and die were Black Americans—it looked a race, gender and class issue because it was. A few years later during Hurricane Sandy, it was clear that the US had learnt nothing from the traumatic upheaval wrought by Katrina. In this instance, it appears that nearly all might be left behind, but that the social binaries of race based poverty and gender would endure, starkly.

Though often hampered by resource constraints, most African countries have a better track record of deploying state support and resources to deal with the upheavals of disease and the aftermath of war. The Ebola virus, the ongoing HIV/AIDs pandemic and malaria have provided lessons in the folly of denial, the importance of protecting health workers, of accessible and low-cost medication, robust public education, and open and consistent communication. So much of what seems like basic sense has been found wanting in the handling of Covid -19. The news that British Prime Minister Boris Johnson has tested positive after robust handshaking whilst we have been advised to keep a distance and wash our hands shows a reckless leadership deficit during a defining moment.

The last forty years of globalisation as market orthodoxy has commodified health care. The globalisation of trade is central to health services that have become a tradeable commodity in an era in which many States have disinvested from health services altogether. Like education, access to water and electricity, health provision has been a casualty of structurally adjusted States and the curve between the global South and the North has been exposed during this crisis as the UK and the US, often considered to be ‘developed’, have again been found weak and unprepared for a health trauma of this scale. The prescripts and onerous impacts of conditional aid and state disinvestment in social provision have long been felt by African and Latin American countries.

Globally, states are all experiencing the impacts and limits to free market logic. Though characterised by many as the great equaliser, a time when States are equally fragile across the global north and global south, the true genesis of this global devastation is northern capitalism and demobilised States. Structural adjustment as a project has evolved and is a continuing mantra of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. Both recently unveiled their market driven response of emergency loans targeting developing countries primarily in the Global South. The depleted health and sanitation systems in many countries is testimony to the devastating success of neoliberal globalisation in immobilising national state capacities.

Following structural adjustment programmes, most health care and essential services – including water, energy, education – may be removed from state purview for cost recovery arrangements. In this scenario private companies invest their funds in return for state guaranteed monopolies and price control, further dispossessing and excluding vulnerable communities. Public Private Partnerships – which are essentially polite privatisation – have existed for centuries, thriving even more when States are weakened. These have also become the easy allies of disaster capitalism as seen in the wake of Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy where education and energy supplies were privatised, monetised and removed from the domain of public good.

Despite decades of state neglect, social apartheid and various global traumas, consensu has formed on closing down public movement and curbing personal freedoms to address the War called Corona. The introduction of “lockdowns” with no tangible provision for social safety nets has posed significant risks to workers in the parallel economy, internally displaced persons, the working poor, fragile urban communities and other marginalised sectors.

Notwithstanding outsourcing their most fundamental functions to the private sector and ignoring their duty to distribute social and economic benefits to the most vulnerable in society, States are now calling on us to trust them as they invoke martial law. This has resulted in the largest shutdown of the last century. Unlike the two European wars (1914-1918 and 1939-1945) the impact of this situation is not localised to a few European nations, the Soviet Union, Australia, Japan and the United States. Globalisation has transmitted both the disease and uniform approaches to problem solving.

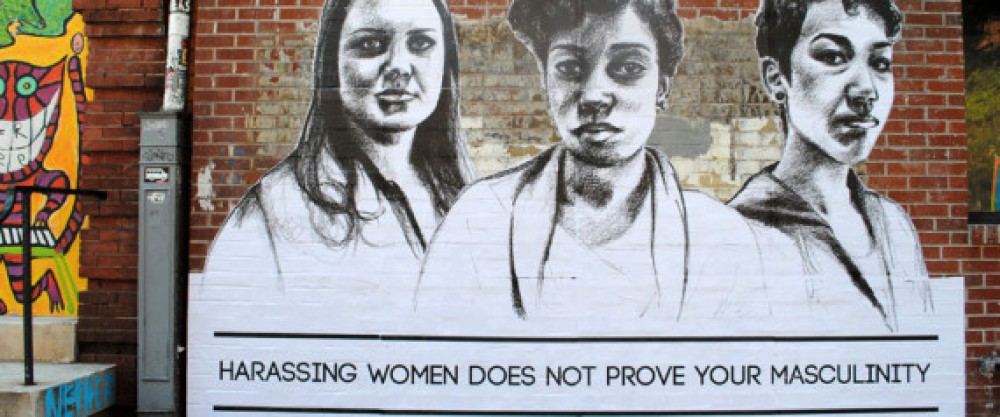

Students of civil liberties, human rights and social cohesion have opined on the politics of enclosure in times of war and peace. Even during enclosed times, States exhibit inherent biases and weaknesses that maintain privilege for corporate and masculinised interests. South Africa has lived through public control in living memory, and distrust of the State and state security is still embedded in social discourses. Like many other countries, the spectre of securitisation of human mobility sits badly, particularly as we still recall the dehumanising policing of colonial Apartheid exemplified by the Sharpeville Massacre, Soweto Uprising and Uitenhage massacres among many. Troublingly, the Marikana Massacre and the violence against the #FeesMustFall activists illustrates that the State can be a brutal personality regardless of the supposedly progressive underpinnings of the Government in power.

At the time of writing, South Africans are required to carry Identity Books in case we are stopped by the police or army when going to buy groceries or medical supplies. Once more, personhood is linked to a form of the much reviled Apartheid Passbook. It is deeply unsettling, albeit necessary, that states are containing us to control a warlike virus that might have been prevented had the same States not neglected and commodified health care so shamelessly. The same could be said of nearly every country battling the Corona pandemic.

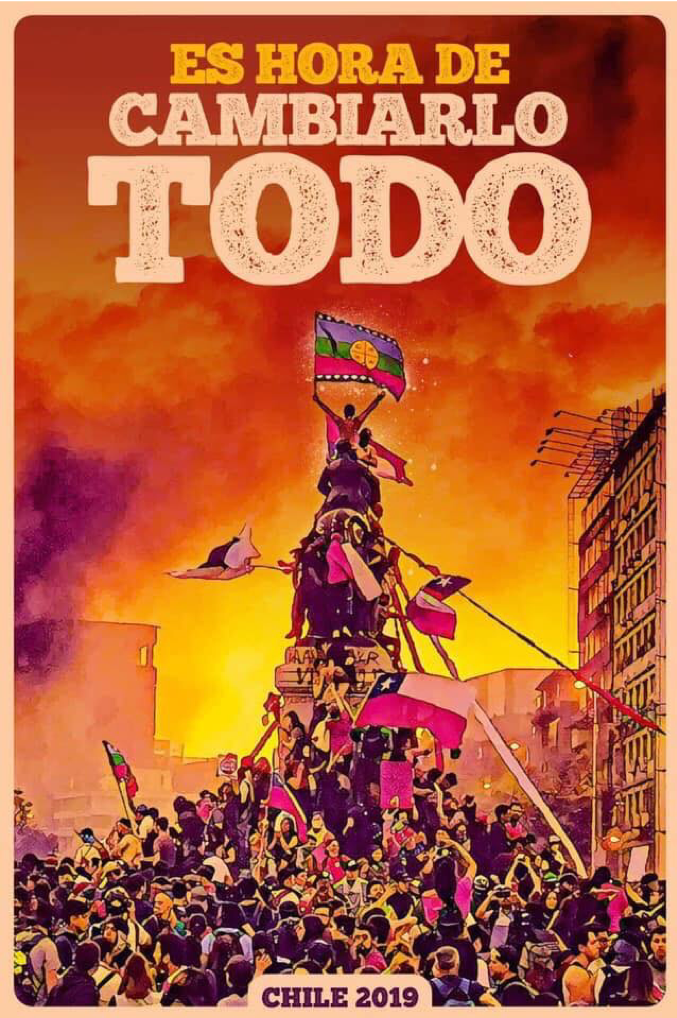

Whilst allowing already problematic Father States to lead us through very complex terrain, we recall that States are often inclined towards repression. Public order policing and martial law have often been the retreat of authoritarian regimes, evoking public safety, order and emergencies real or created to control citizens and residents . Late last year the Chilean government clamped down on high school protestors who demanded that the State provide cost effective public transport. The escalating rage resulted in something resembling a nationwide, cross-issue movement against price increases, poor social services, and unemployment. It remains to be seen whether the promise of a constitutional reform will quell public dissent. France has faced similar protests on public pension funds and the retreat of the State in maternity clinics and postal services . Macron effectively ‘closed down’ France nearly two weeks ago. In the midst of their lockdown, thousands marched against him the day before local government elections. While States might have found the opportunity to indulge their regressive impulses during the time of Corona, not all of us are amnesiac about how we got here.

(Photo Credit: Daily Maverick / EPA – EFE / Kim Ludbrook)