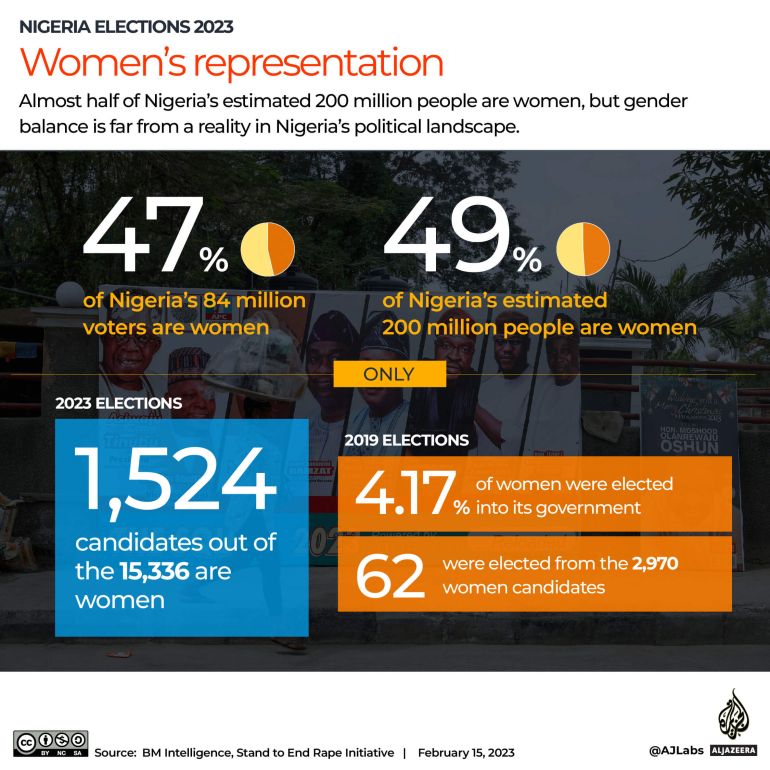

#NigeriaDecides. For the last couple months, the hashtag has been everywhere. Well, if not everywhere, in many places. In a much-anticipated election, Nigeria voted yesterday, February 25, 2023, for President and members of the National Assembly. Leading up to vote, a number of news agencies ran articles with headlines like “What you need to know”, “What’s at stake”, “What to Know”, “what are the issues”, and the list goes on. While these articles focused on the youth vote, economic insecurity, military insecurity, they did not include any mention of gender, of women, despite that actually being a topic of more than passing interest among Nigerians, especially Nigerian women. So, where are the women in Nigeria’s elections? Sadly, severely underrepresented.

This year, one woman, Princess Chichi Ojei, of the Allied Peoples’ Movement, ran for President or for Vice-President. That’s out of 36 presidential candidates and running mates. In the last election, 2019, 28 of the 146 presidential candidates and running mates were women. From 2019 to 2023, then, the percentage of women among candidates for top positions has gone from 19.2% to 2.8%. Of the 1,100 candidates for Senate seats, 84 are women, or 7.6% of those running. As Africa Check noted, “Our factsheet on the status of women in Nigeria shows that since the country’s return to democracy in 1999, the share of women in the federal legislature has remained well under 10%. Sadly, this will not change in 2023.”

In Nigeria and across the continent, as people followed the lead-up to the elections, many asked, ”Where are the women?” For example, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, former President of Liberia, and K.Y. Amoako, founder and President of the African Center for Economic Tranformation, wrote, “Women’s progress toward high leadership positions unfortunately leaves much to be desired. Since it gained independence in 1960, Nigeria has not had any women presidents or vice presidents. It has not elected any female governors across its 36 states. Its proportion of women representatives in both legislative chambers does not exceed 7%. The country’s national average of women’s political participation has remained around 6.7% in elective and appointive positions, far below the global average of 22.5%. In Nigeria, women and girls account for half of the population, and therefore represent half of its potential as an African nation. For Nigeria to prosper and progress, it must increase the representation of women in decision-making positions. Nigeria’s equity challenge did not arise because of a lack of leadership potential in its women. Nigerian women are a shining beacon of public leadership on the global stage.”

Nigerian women, individually and in organizational spaces, have been aware of and decried the current situation. In January, Chimamanda Adichie asked, “There is … something sad about the idea that we haven’t had a woman governor in this country. It’s wonderful that we are celebrating the possibility [of having one soon] but why has it taken so long?” Ayisha Osori, former candidate for National Assembly, noted, “Elections in Nigeria are monetised and transactional, and women are already socially disadvantaged considering that in Nigeria, the fastest way to be rich is to be in government. If women are not in politics then they cannot raise money and if they cannot raise money, then they cannot be in politics.” Mufuliat Fijabi, CEO of Gender and Election Watch, a Nigerian NGO, noted that this election is part of a trend, “If you look at the global average practices, we are not where we should be in terms of inclusion of women in leadership and decision-making positions. The number of female candidates in this election is 7.8 per cent which means it’s very few and if we are not careful, the number may decrease.”

Speaking of the National Assembly, the outgoing legislature has 469 members, of whom 21 are women. 4.4% of the legislature are women. That’s the legislature that in March 2022 rejected five gender bills that would have provided special seats for women at the National Assembly; allocated 35% of political position appointments to women; created 111 additional seats in the National Assembly and the state constituent assemblies; and committed to women having at least 10% of ministerial appointments. The Assembly rejected them all: “This is a tragedy for Nigerian women.”

Nigerian women have experienced both a gradual erosion of their position and progress in elected and appointed positions, as well as a more recent open backlash. At the same time, the international press, with the exception of Al Jazeera, has largely kept silent on the situation, despite claiming to offer necessary information about the Nigerian election. What you need; what’s at stake; what to know; what what what what what. What I know is where are the women in (the news coverage of) Nigeria’s elections?

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Infographic Credit: Al Jazeera)