Jerry Ekandjo is Namibia’s Minister of Youth, National Service, Sport, and National Service. On Wednesday Jerry Ekandjo rose in Parliament and told the members that Namibia should respond to the high rates of teenage pregnancy by “reintroducing” the practice of taking pregnant teenagers, binding them in grass, and setting them alight. This would serve as a warning to other girls and young women. Namibian social media exploded in protest. On Thursday, Jerry Ekandjo tried to explain: “I made a joke that in the past, those who fell pregnant before they were married were rolled in grass and set on fire, leading to the name ‘oshikumbu’, to set an example to others. Is that something worth publishing in the newspaper. I was just joking. I did not mean that people must be burned in reality for falling pregnant. I am a joking person.” Whether Jerry Ekandjo is, or is not, a joking person is irrelevant. Violence against girls and women is not a joke.

In his various recent studies of young Namibians’ perceptions of sex, sexuality, HIV and AIDS, Pempelani Mufune, former head of the Department of Sociology at the University of Namibia, noted that young people today use“oshikumbu” as “slut” and “bitch”, a derogatory name for a never-married-woman-with-children. Under the smoke screen of tradition, Jerry Ekandjo appeals to violence against women as acceptable in the service of the nation.

Jerry Ekandjo made his statement in response Elma Dienda, a member of Parliament and a teacher, who urged her colleagues to rethink policies on teenage pregnancy. Dienda called for real sex and reproductive health education in schools and she called for an end to denying pregnant students the opportunity to sit for exams. Ekandjo’s response was, first, that pregnant students must be punished more harshly, and then he launched into his Oshikumbu Manifesto.

In 2000, Jerry Ekandjo was Namibia’s Home Minister. In an address to 700 new graduates of the police academy, Jerry Ekandjo to the new officers that they should “eliminate” gay and lesbian people “from the face of Namibia.” As this week, activists and many in Parliament then were also enraged.

On the same day Jerry Ekandjo “explained” his statement, Pakistani activist writer Rafia Zakaria explained women’s empowerment: “The term was introduced into the development lexicon in the mid-1980s by feminists from the Global South. Those women understood `empowerment’ as the task of `transforming gender subordination’ and the breakdown of `other oppressive structures’ and collective `political mobilization.’”

Elma Dienda understands that women’s empowerment means transforming gender subordination, and that it’s no joke. Keeping women and girls out of school is no joke. Threatening violence against women and girls is no joke. According to Namibia’s Ministry of Education, in 2015, 1843 girls left school because of pregnancy; in 2016, that number more than doubled, reaching 4000. That is no joke.

In November, SWAPO, the majority party in Namibia, will hold its congress. Most people think that Jerry Ekandjo will run for SWAPO President. If he wins, he would almost certainly become the next President of Namibia, and that is no joke. Tell Jerry Ekandjo, and all the leaders of the world, that violence against women and girls is not a joke!

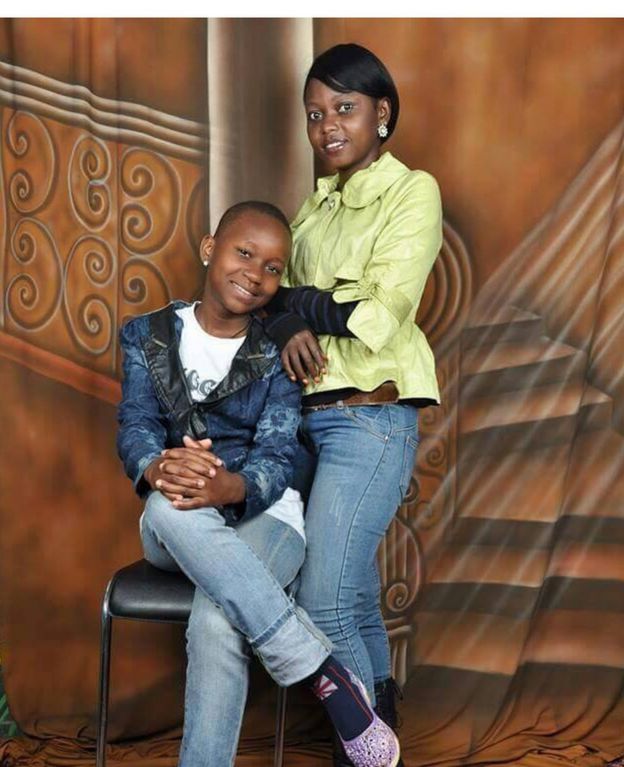

(Image Credit: Namibian)