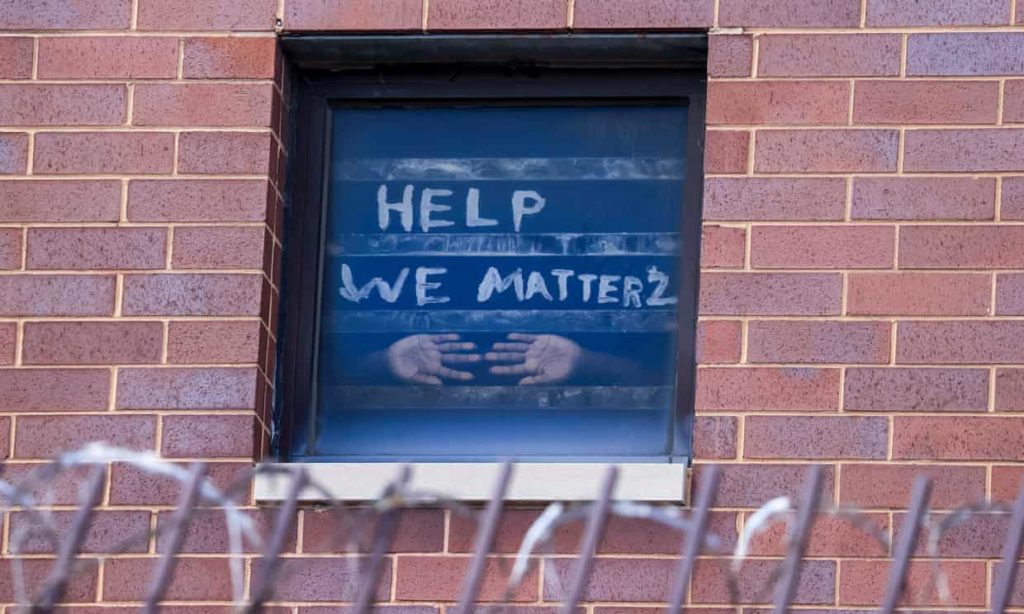

For over a year now, the news media have covered a class action lawsuit concerning the Federal Correctional Institution, Dublin, which argued that the women incarcerated at FCI-Dublin were routinely subjected to sexual violence, harassment, intimidation and other forms of brutality. This lawsuit is only one of over 60 that have been filed against FCI-Dublin since 2021, all claiming a pattern of sexual violence in the institution. In April, FCI-Dublin was shut down, and the women were moved to other institutions all over the country. What if it’s the same everywhere?

Thanks to a recent, and some would say consequential, election, the government of the United Kingdom changed hands from Tory to Labour. The Labour government has “discovered” that the prisons are a toxic mess. This week, UK Ministry of Justice published its latest Safety in Custody report, looking at deaths up to June 2024, self-harm up to March 2024: “In the most recent quarter, self-harm incidents were up 8% to 19,418, and the rate was up 9% (a 2% increase in male establishments and a 29% increase in female establishments) …. The rate is more than eight times higher in female establishments than male establishments …. The rate of assault was 71% higher in female establishments than male establishments.” Why are the rates so high in women’s prisons, and particularly so much higher than in men’s prisons? Nadia spent five months in a women’s prison, which she described as “walking onto the set of One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest … Many of the girls there should not be in prison, they need proper help.” The majority of incidents of self-harm and of assault in women’s prisons are not as violent or severe as those in men’s prisons, but the numbers and rates are higher. What does that tell you? As in FCI-Dublin, the response has been to describe the situation as “a failure”. There was no failure, there was, and is, refusal.

In May, it was reported that the number of deaths by suicide in the Cefereso 16 CPS Femenil de Morelos, the women’s prison in Morelos, had increased by so much that all cases from then on would be investigated by the Fiscalía General de la República, the Attorney General of Mexico. In July, it was reported that almost half the women held in prisons are remand prisoners … innocent until proven guilty … or dead. The United Nations finds this situation “particularly preoccupying.” Again, as in the United States and the United Kingdom, the systematic violence against women is seen as a “failure”. There was no failure. There was simply refusal.

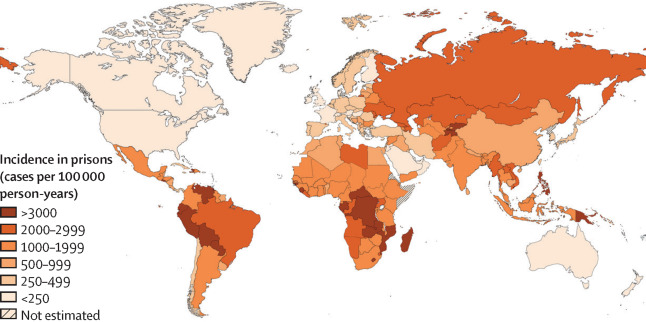

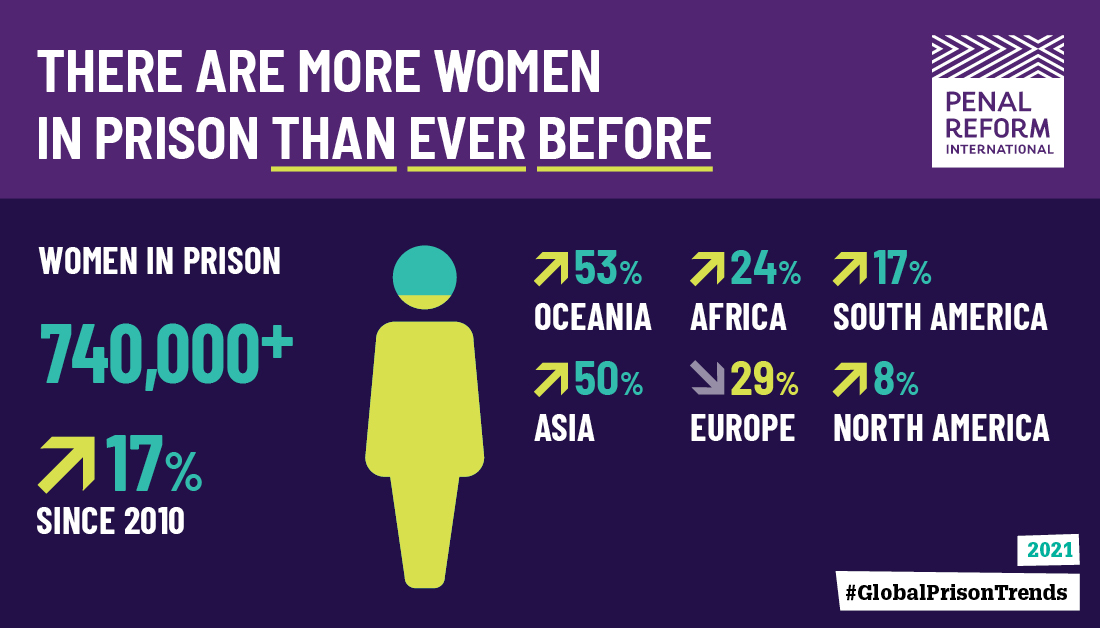

In the global scheme, the women’s prisons of the United States, United Kingdom, and Mexico are not outliers. If anything, they’re viewed as more or less preferable to prisons in many other parts of the world. None of that matters. What matters is justice. Again and again, the State, or the Fourth Estate, “discovers” systemic and systematic violence against women in prisons, jails, detention centers. Each time, shock and dismay are expressed, then “failure” is somberly and solemnly declared, and then … nothing. At best, the individual house of horror is shut down and the women are moved … to another. There is no justice in women’s prisons. There is cruelty in the decision that every act of violence was a sign of failure rather than the system working as it was meant to work, to the detriment and ultimate destruction of women. Otherwise, how else explain the infinite and cyclical redundancy of discovery? Instead of “repairing” the prisons, give the women, and the world, “proper help”.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

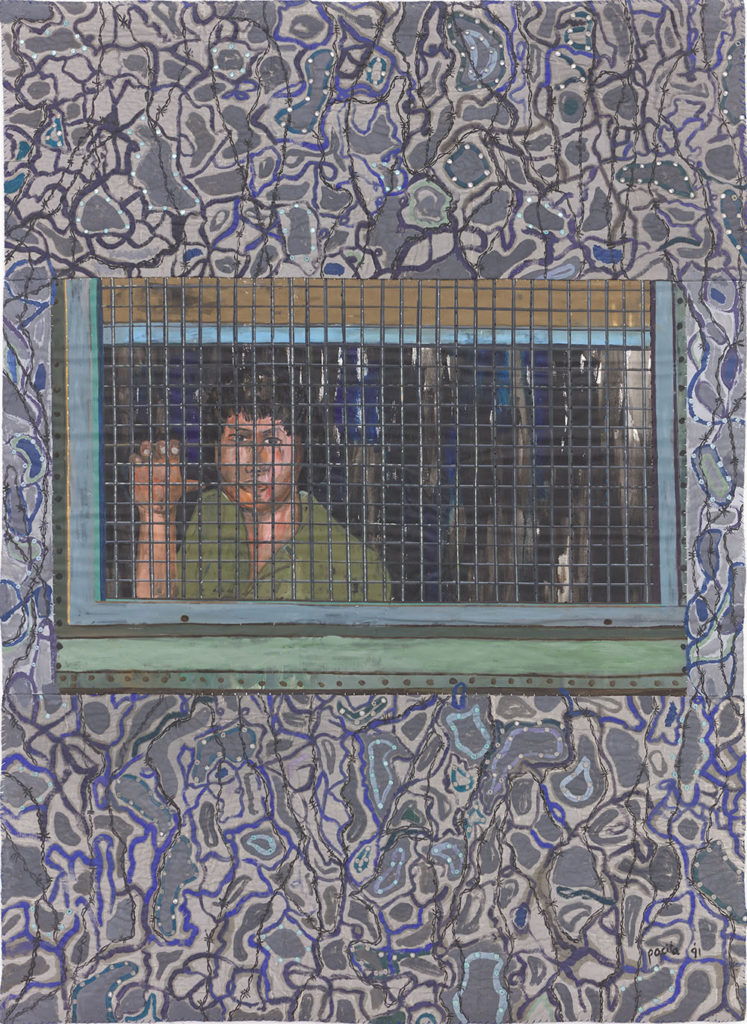

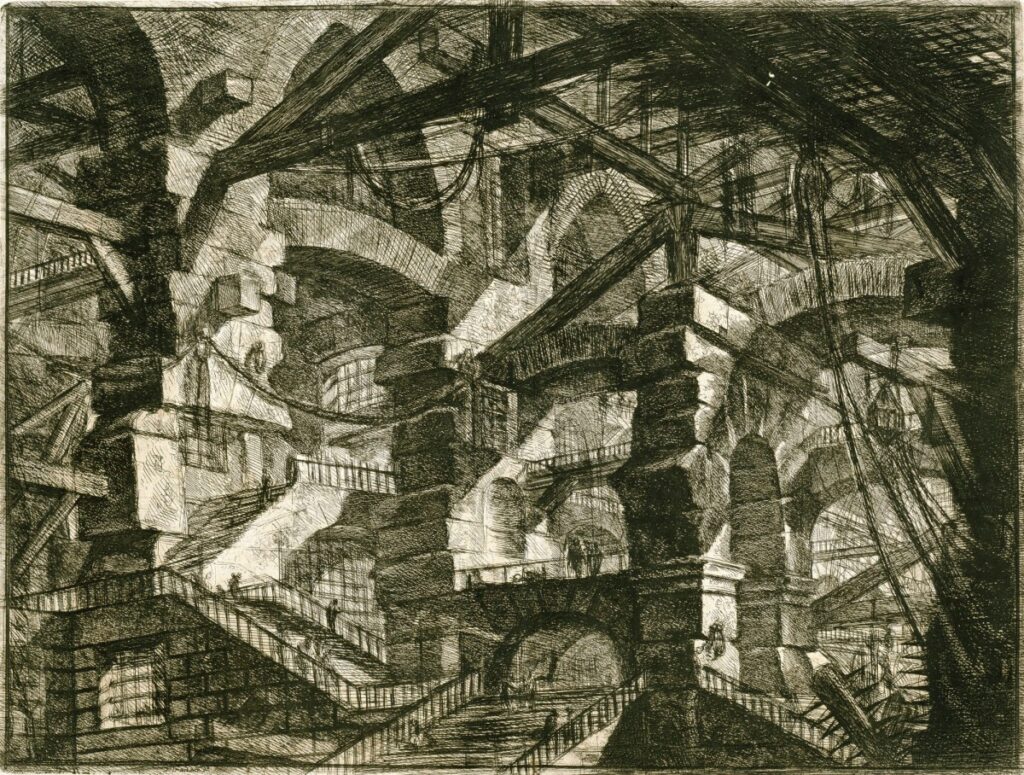

(Image Credit: Giovanni Battista Piranesi, The Gothic Arch / The Royal Academy of Arts)