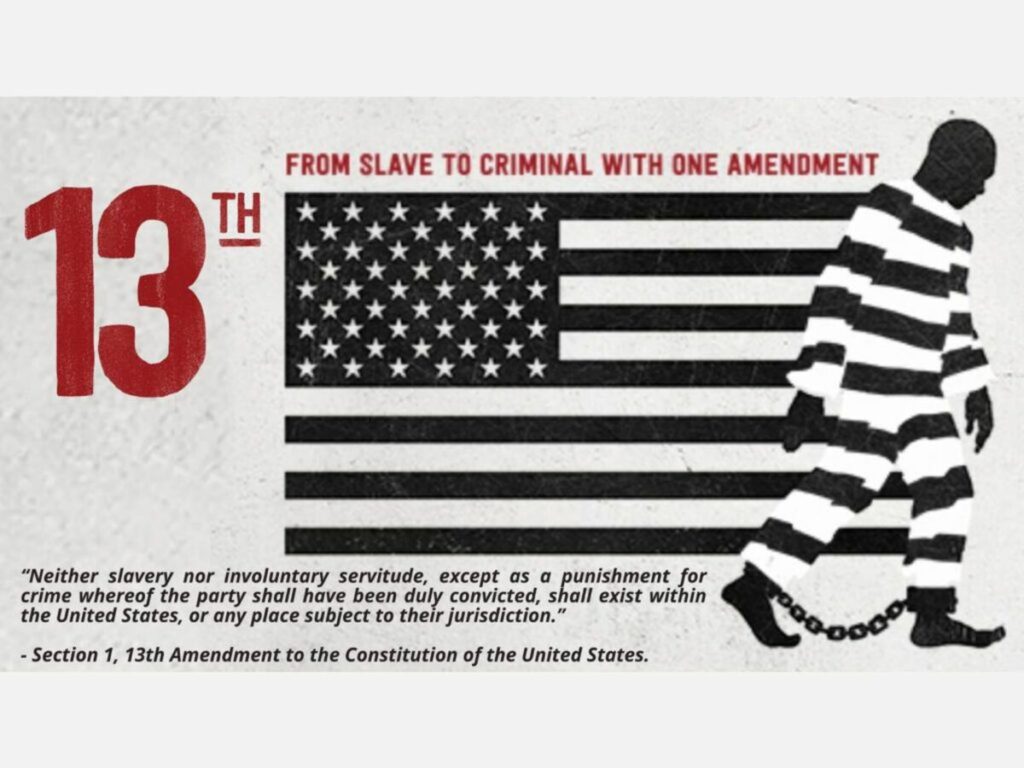

On January 31, 1865, the U.S Congress passed the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution, which reads in its entirety: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.” The Amendment was ratified on December 6, 1865. According to the National Archives, “With the adoption of the 13th Amendment, the United States found a final constitutional solution to the issue of slavery.” Not altogether. There’s the matter of the exception clause, “except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted,” which makes it perfectly legal, even Constitutional, to force incarcerated people to work for little or no pay. Yesterday, January 31, 2024, 159 years later, advocacy group Worth Rises released a study, “A Cost-Benefit Analysis: The Impact of Ending Slavery and Involuntary Servitude as Criminal Punishment and Paying Incarcerated Workers Fair Wages”. Where are the women in this study and in the current world(s) constructed and codified by the 13th Amendment’s exception? Where are the women, and where should they be?

According to the study, “This study projects that while society overall will benefit from abolishing slavery and involuntary servitude in prison, and from paying fair wages for prison labor, those gains will fall disproportionately to groups and communities that have been most impacted by mass incarceration, specifically Black and Brown people, low-income people, and women …. Roughly 47% of incarcerated men and 58% of incarcerated women are the parents of minor children …. 58% of women in state or federal prisons have minor children,103 and most of them are single mothers, thus bearing sole responsibility for their young children …. Women — and Black and Hispanic women in particular — shoulder most of the financial costs of incarceration burdening families and loved ones. A recent study, for instance, showed that family members paid for court-related costs in 63% of criminal cases, and that 83% of these family members were women. The same study also found that 87% of the costs of staying connected through calls and visits similarly fell on women. Based on these data, this study projects that women will indirectly receive much of the economic benefit from fair wage payments to incarcerated workers.” Where are the women? Everywhere all at once and under attack.

While ending slavery and involuntary servitude are worthwhile, laudable and practical goals, is it enough? Consider the news just from the past week.

On Wednesday, the same day the study was issued, The Seattle Times reported, “Washington state has paid $9.9 million to settle a lawsuit by a woman whose cervical cancer grew terminal while she was incarcerated after prison doctors failed to adequately diagnose and treat the disease. In the latest of a series of deadly and expensive health care failures in state prisons, Paula Gardner, who was serving time for drug and burglary convictions, didn’t receive appropriate medical care for more than two years despite tests showing signs of possible cancer — and eventually a scan revealing a growth inside her uterus …. The settlement money will benefit Gardner for what remains of her life, as well as her two sons, who were also plaintiffs in the lawsuit.”

On Monday, The Argus Leader reported, “The state [South Dakota] is facing a record average daily population of more than 600 women in the state’s two women prisons. That’s nearly double the prisons’ daily capacity.” Department of Corrections Secretary Kellie Wasko commented, “I do worry a little bit about the female institution if we don’t do something.”

Do something. More often than not, the response to overcrowding is to build more prisons, this even though Secretary Wasko made it clear that sentencing guidelines and, secondarily, substance abuse account for the fact that people were incarcerated in the first place. Building more prisons won’t address the injustice of the sentencing system nor will it address substance abuse.

Do something. Two weeks ago, in England, a court of appeals did something: “The court of appeal has quashed the prison sentence of a heavily pregnant woman so that she can give birth safely, in a case hailed as a landmark by campaigners.” Instead of the sentence she had received from a criminal court, five years for possession of a firearm and ammunition and serving two and a half years in prison, the judges gave the woman a two-year suspended sentence with a rehabilitation requirement.

The case occurred at all because the pregnant woman’s mother feared for her daughter’s life and contacted Level Up, “a feminist community campaigning for gender justice in the UK”. Level Up campaigns to keep pregnant women out of prison. Level Up gave the pregnant woman support and assistance. After the judges’ decision was rendered, Janey Starling, Level Up co-director, said: “This landmark judgment marks a sea change in sentencing practices. Several other countries do not imprison pregnant women or new mothers and England’s courts are beginning to catch up. Prison will never be a safe place to be pregnant. The prison ombudsman, Ministry of Justice and NHS have declared all pregnancies in prison as high risk. This means that when a judge sentences a pregnant woman to prison, they are sentencing her to a high-risk pregnancy. That is unconscionable.”

Slavery is unconscionable. Involuntary servitude is unconscionable. Refusing care is unconscionable. Toxic, life endangering overcrowding is unconscionable. Sentencing someone to high-risk pregnancy is unconscionable. Do something about it. Close the prisons and create the scales of justice anew. 159 years is too long.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Image credit: 2nd Life Media Alamogordo Town News) (Photo Credit: Level Up / Elizabeth Dalziel)