Under the military dictatorship of Pinochet in the 1970s, economic austerity was placed on the people of Chile. Under the guise of reform, neoliberalist measures on the people of Chile were implemented, resulting in widespread economic hardship and massive wealth inequality. For thirty years, the working class and indigenous populations in Chile suffered under Pinochet’s market-driven economic model, which privatized pensions, health and education. Unions were decimated as was the public education system, and public services were shifted to private enterprises. Chile remains a country with the highest cost of living in South America and is considered one of the most unequal in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development group of nations.

The recent uprising occurring in the country began as a protest against a hike in metro ticket prices and quickly escalated into a massive revolt against the significant income inequality in the country. The proposed transit fare rate would have risen to nearly 1.20 a ride, a 4% increase; a significant burden placed on low-income families who spend 13% of their budgets on transportation, and retirees who are forced to survive on a pension that is below the minimum wage.

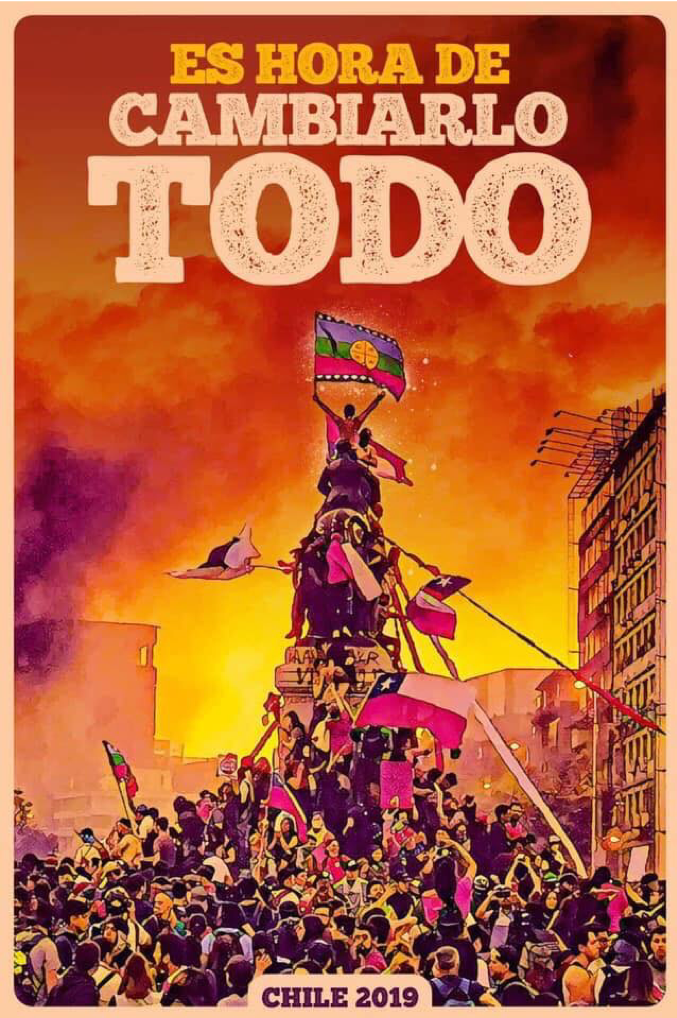

The response to the simmering anger over the rising cost for the poor and old? That they just get up earlier and leave for work before seven in the morning to avoid paying the rush hour rate. Now after a million people took part in a demonstration on October 25th, thousands of other protests from poor, young, students, indigenous populations, and union workers, the government has finally realized that squeezing more money and work and time out of the poor may not be the most competent economic model.

Piñera has walked back on the neoliberal policies that have entrenched inequality in Chile, but they are not enough. As the last nail in the coffin of Pinochet’s cruelty, his constitution is echoes the continuing destruction of working people and the elderly in the country. While Piñera has moved to raise the minimum wage and pensions, demand pay cuts from government officials, and fired his entire cabinet, many see these gestures as token and symbolic at best – Pinochet’s constitution is still in play – and have demanded a truly democratic society, where the power is not vested only in the hands of the wealthiest and the out of touch. And the people are not backing down, even after the president’s paltry promises.

Meanwhile, how are American citizens reacting to our overwhelming inequality; where are the uprisings that should have been in place after the NYC’s fare enforcement? Where is the anger when poor men and women are tackled and tased for not paying $2.00 while the city employees four cops at almost $80,000 a year to brutalize them? Will we ever be as revolutionary, or will it happen too late?

(Photo Credit: CanalC)