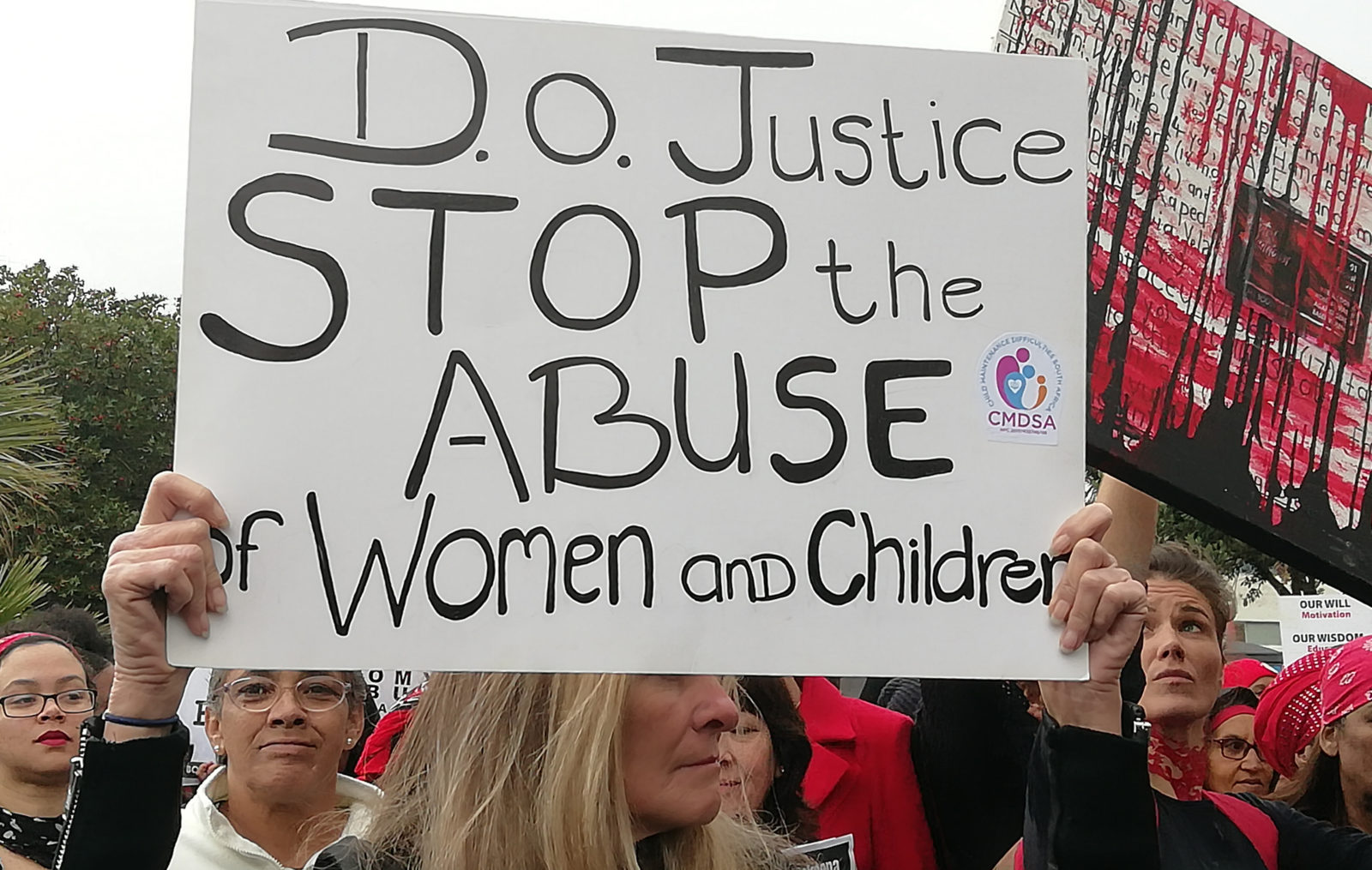

In case we needed any reminder, this week has already demonstrated that rape culture is expanding, intensifying and globalizing. Yesterday, across Argentina, thousands marched and protested violence against women, femicide, and rape. They marched under the banner of Ni Una Menos and Justicia Para Micaela. Micaela Garcia was a 21-year-old feminist activist who dedicated her life to the struggle to end femicide and violence against women. Last week, she was raped and murdered. In India, human rights activist Bondita Acharya criticized the arrests of three people for the crime of possessing beef. Very quickly after Bondita Acharya expressed her views, she was threatened with acid attacks, rape, and death. According to Bondita Acharya, “They threatened me with death, rape, acid attacks, and also hurled sexually explicit abuse to defame me … I also feel the anger was directed at me because I am a Brahmin and a woman.” And in South Africa, yesterday, a prominent cartoonist decided to make his point by graphically describing the gang “rape” of South Africa. The nation was drawn as a Black South African woman, held down by three men.

Women have responded forcibly and directly to each and all of these atrocities. In Argentina, women mobilized by the thousands. As Marta Dillon, of Ni Una Menos, explained, “It is a day of mourning, but we know how to turn pain into power.” Nina Brugo added, “We are going to take revenge for Micaela by getting organized.” In India, Women against Sexual Violence and State Repression strongly condemned the persecution and harassment of Bondita Acharya, and are pushing the State to take action. Others have joined in the cause. In South Africa, women have led the charge against the abuse of their bodies and lives. Kathleen Dey, Director of Rape Crisis Cape Town Trust, capturing the feelings of many, wrote, “The impact of rape on survivors is severe, many will lie awake at night and are not be able to sleep or eat properly for days because of the powerful emotions they feel. Feelings of fear, anxiety and vulnerability in particular provide the kind of undermining emotional preoccupation that often prevents women from working, studying or parenting effectively. Reliving rape is easily triggered. It disturbs and disrupts everything rape survivors do and distresses the people close to them who feel helpless to do anything to mitigate these powerful feelings. The fact that these same women often face the stigma of being socially disgraced when they speak out about being raped is another example of rape culture. Challenging rape culture in South Africa and asking ourselves what a culture of consent might look like and how we would build that culture instead would be a worthy subject for the media.”

It would be a worthy subject indeed. In 1986, feminist political economist Maria Mies wrote, “It is a peculiar experience of many women that they are engaged in various struggles and actions, the deeper historical significance of which they themselves are often not able to grasp. Thus, they do in fact bring about certain changes, but they do not ‘understand’ that the changes they are aiming at are much more far-reaching and radical than they dare to dream. Take the example of the worldwide anti-rape campaign. By focussing on the male violence against women, coming to the surface in rape, and by trying to make this a public issue, feminists have unwittingly touched one of the taboos of civilized society, namely that this is a ‘peaceful society’. Although most women were mainly concerned with helping the victims or with bringing about legal reforms, the very fact that rape has now become a public issue has helped to tear the veil from the facade of so-called civilized society and has laid bare its hidden, brutal, violent foundations. Many women when they begin to understand the depth and breadth of the feminist revolution, are afraid of their own courage and close their eyes to what they have seen because they feel powerless vis-à-vis [the] task of overthrowing several thousand years of patriarchy. Yet the issues remain. Whether we – women and men – are ready or not to respond to the historic questions raised, they will remain on the agenda of history. And we have to find answers to them which make sense and which will help us to restructure social relations in such a way that our ‘human nature’ is furthered and not crushed.”

Thirty-one years later, rape remains on the agenda of history but too often not on the agendas of nation-States nor organizations nor the media. We still await that revolution.

(Photo Credit: José Granata / EFE / El Pais)