Last Monday, Reclaim the City reported, “Reclaim the City has been approached by a woman (who wishes to remain anonymous) whose rent has been increased by the City of Cape Town (‘the City’) by more than 2000%. She has rented a City council home in Salt River from the City of Cape Town since 1995. When her and husband moved in, they signed a lease agreement with a rental of R220 per month. The house was an uninhabitable mess. Over the years, they improved, fixed and maintained the property at their own expense. Due to minor rental increases, her rent is now R243.81. She has never defaulted on her monthly payments and has lived happily in her home for the last 24 years. In August 2019, the City of Cape Town sent her a letter saying they are increasing her rent to R5 500 per month. This is an astronomical increase from the R243 she is currently paying.” For millions across the globe, this is an all too familiar story, but what exactly is the story? In what world is it acceptable that anyone receive a rental increase notice of more than 2000%?

1995, Cape Town. Apartheid is officially ended, and, across the country, the new South Africa is on everyone’s lips, minds, and hearts. Reconstruction and Development Programme community flora are meeting everywhere … or almost everywhere. There’s a new President, a new Parliament, and a new dispensation. A rainbow hovers over the nation and over the Mother City, as Cape Town is called.

While some of this picture is accurate, missing are the plans to “re-develop” Cape Town, to turn Cape Town into a thriving “global city”, replete with a metropolitan economy largely driven by real estate development. In the midst of all this, a couple move into public housing, twenty-four years ago, in the working class neighborhood of Salt River, a neighborhood known largely for second-hand shops, a diverse array of working class communities, and Community House, a center for community and labor organizing. It’s also known for the empty textile and garment factories that closed during the 1980s, when the apartheid regime invested heavily in Export Processing Zones that gutted the vibrant garment and textile economies of the Western Cape.

So, this couple moves in, signs the lease, fixes the place up (at considerable expense to themselves), never misses a payment, makes a home for themselves and for their neighbors. This couple survives and makes a life of dignity and self-respect. For their great labors and contributions to the municipality’s well-being, they are rewarded with amounts to an eviction notice.

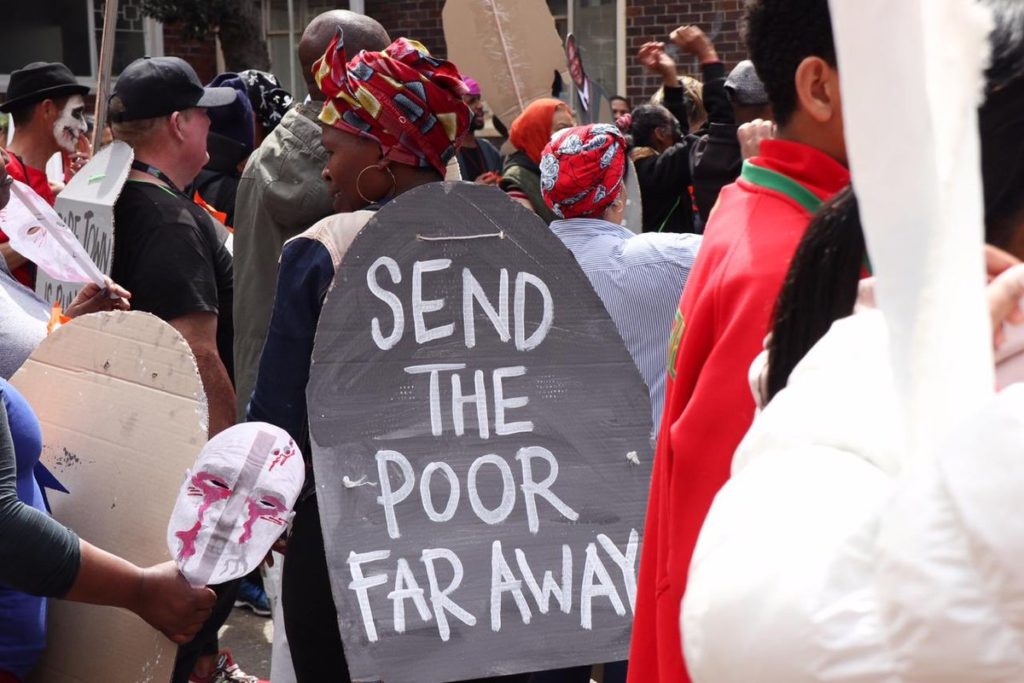

The couple have appealed, Reclaim the City and their supporters are organizing to help them remain in their home, the City continues to threaten eviction. Given the recent pattern of “spiraling” evictions in the Cape Town region, this comes as no surprise. As Reclaim the City notes, “If anyone needs more proof that the City is anti-poor and anti-black, this woman’s exorbitant rent hike is case and point.”

Anti-poor, anti-Black and committed to growing inequality as the key to urban development. For millions across the globe, and especially those living in so-called urban cities driven by service sector economies and predatory real estate development, this is an all too familiar story. But what exactly is the story? Remember, this working-class couple in Cape Town live in public housing. Their landlord is the City. The City raised their rent by over 2000 percent. When they responded and asked for help, the City threatened them with eviction. In this instance, eviction is exile, because a couple seeking to pay less than 300 rand a month won’t find anything anywhere near livable in Cape Town.

What is public housing, if this is how the State acts? What is the public, if the State has committed to exploiting, oppressing and, if all else fails, assaulting the working populations who make it possible for the Public to function? What exactly is the story? That question has been answered recently in the streets of Ecuador, Sudan, Chile, Lebanon, Hong Kong and beyond. This story is not yet over, neither the local one in Cape Town nor its global counterpart; the struggle continues. Apartheid gentrification, gentrification that condemns working people to forced removals to distant regions, haunts the world. In what world is it acceptable receive a rental increase notice of more than 2000%? Our world. Another world must be possible.

(Photo Credit: Twitter)