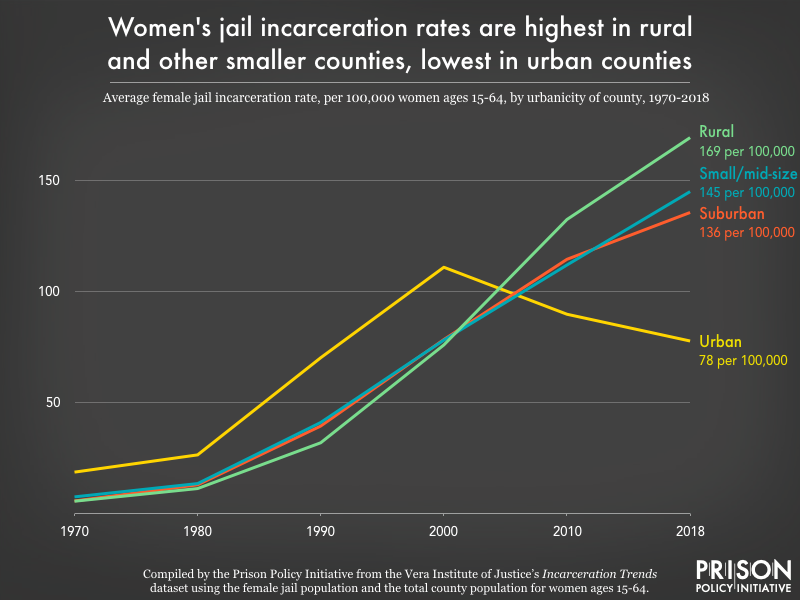

Tomorrow, Sunday, July 18, the United Nations will celebrate Nelson Mandela International Day. With that in mind, on Friday, July 16, the United Nations released its first global research data on the state of prisons over the past twenty years. It’s predictably grim, especially for women. Globally, one in three incarcerated persons has not been found guilty by a court of justice. Either they are awaiting trial or they are simply being held. This means overcrowded conditions, which means spikes in covid, as we’re seeing this week in Missouri’s prisons. A surge in prison population = a spike in covid. For women, this means a global war on women and girls. From 2000 to 2019, the number of prisoners worldwide increased by more than 25 per cent. During that period, the number of women in prison increased by 33% while the increase for men was 25%. According to the UN, “the female share of the global prison population has increased, from 6.1% in 2000 to 7.2% in 2019.” What does this trend look like in the United States? Catastrophic, and especially so for women being held in jails.

According to the latest jails report from the U.S. Department of Justice, from 2008 to 2018, the female jail population increased by 15% while the male population decreased by 9%. From 2005 to 2018, the female incarceration rate rose by 10%, while the male rate of incarceration dropped by 14%. Between 2008 and 2018, the female jail population rose by 15%, the male jail population dropped by 9%. In terms of criminal justice systems and, specifically, policing and incarceration, the past twenty years have been catastrophic for women globally and nationally.

What does catastrophe look like? According to the most recent U.S. Department of Justice report on mortality in jails, “In 2018, females held in local jails had a higher rate of mortality … than males.” Chronic diseases, especially respiratory infections, cancer, heart disease; suicide; drug and alcohol related problems are `credited’ as cause of death, but the cause of death is jail itself. While the pandemic has exacerbated the situation, the United Nations report covers two decades, 2000 to 2019, and this is only the second time since 2000, when the Department of Justice started reporting on the situation in jails across the United States, that women had a higher jail mortality rate than men, and that was in 2018, before the pandemic.

Tomorrow, July 18, is Nelson Mandela International Day. Earlier this week, July 13, marked the sixth anniversary of the death of Sandra Bland, in a jail in Texas. Since then, the situation for women in jails across the United States has only worsened. The UN report concludes: “Measures can be taken to counteract the relative increase in the female prison population, including the development and implementation of gender-specific options for diversion and non-custodial measures at every stage of the criminal justice process. Such measures should take into account the history of victimization of many women offenders and their caretaking responsibilities, as well as mitigating factors, such as lack of a criminal history and the nature and severity of the offense.” In other words, find and enforce ways of keeping women out of jail. How many more women must die before we hear and act on this common and evidence-supported sense?

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Infographic Credit: Prison Policy Institute)