A man with a bachelor’s degree has accredited knowledge while a woman with a doctoral degree merely professes knowledge. At least, that’s what Joseph Epstein and his acolytes would have you believe. In his recent Op-ed in the Wall Street Journal, Epstein sets out to reproduce the terms of Enlightenment thought in which a white (and white-passing) man is the prototypical human subject, having reason, with a white woman’s claim to reason as fraudulent: “Any chance you might drop the ‘Dr.’ before your name? ‘Dr. Jill Biden’ sounds and feels fraudulent, not to say a touch comic.” That he casually mentions being referred to as ‘Dr. Epstein’ in academia and by scientists recalls how men, at various stages of knowing and accomplishment, are legible as experts in the eyes of the patriarchy. Despite my belief that experience can have equal intrinsic value to formal education – that someone with a bachelor’s degree and experience can be just as knowledgeable and impactful as someone with a doctorate – patriarchal norms are responsible for gender asymmetries that hail men as having legitimate knowledge while vilifying women’s knowledge as fraudulent.

Imani Perry’s groundbreaking work in Vexy Thing: On Gender and Liberation urges us to reconceptualize patriarchy in order to uncover how it operates as a system that produces, structures, and stratifies categories of non-personhood. White women are human-adjacent, caricatures of white men whose doctoral prefixes denote real knowledge. Affixing ‘Dr.’ to a woman’s name is an affront to the disciplinary arm of patriarchy, misogyny, which is levied by folks like Epstein to reinstate men’s predominance as legitimate knowers. Some have narrowly interpreted this piece as emerging from a disgruntled senior with antiquated views on “Dr.” being the preserve of the medically trained. I’m more inclined to read this drivel as that which replicates the grammar of misogyny in the service of patriarchy, a practice that is very much à la mode.

Distinguishing between misogyny and sexism, Kate Manne, author of Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny says, “sexism is taken to be the branch of patriarchal ideology that justifies and rationalizes a patriarchal social order, while misogyny is the system that polices and enforces its governing norms and expectations.” In his op-ed, Mr. Epstein addresses Dr. Jill Biden in the second person, and employs the language of misogyny in his policing of her title and disavowal of her knowledge. For Epstein, Dr. Jill Biden disappears as a woman through a title that puts distance between her as a person and her relationship to a man…and not just any man, the man: President Elect Joe Biden. He will become, like many before him, the ultimate symbol and agent of patriarchal dominance. Knowing this, Mr. Epstein attempts to ‘rescue’ and foreground her womanhood by collapsing and tethering her identity to her husband. She is not Dr. Biden, she is Mrs. Biden. And in order to close the distance between himself and this doctoral holding woman, he infantilizes her by referring to her as “kiddo” and personalizes his address by calling her “Jill.” It is a disgusting move that reeks of condescension. A ‘watch-me-put-you in-your-place kiddo’ kind of move.

Using the language of fraudulence becomes a way of policing womanhood. A woman who is threatening to the patriarchy proudly goes by Dr. so and so. Another mitigates patriarchal anxiety by elevating her position as ‘wife’ and hiding the credentials that make being a wife seem secondary. What makes Epstein’s comments even more significant is that Dr. Jill Biden will soon be ascending to one of the most hallowed sites of femininity in the world: the First Lady. It is imperative for many that it remains a site that fixes women’s subordinate status to men in every respect. What would it mean for the wife of a president to demand that she be seen primarily through the lens of her own knowledge and worldmaking rather than through her relation to her husband? Would a First Lady who didn’t take her husband’s last name have committed an even more egregious sin?

It is somewhat comforting to see the outpouring of support for Dr. Biden, with many academic women on twitter deciding to go by ‘Dr.’ in their Twitter bios in solidarity. One such person tweeted: “Added ‘Dr’ to my profile, wearing my doctorate with pride. So #JosephEpstein and other bitter misogynists can crawl back to the 1930s. Doctorates are not easy, @DrBidenshould be proud of her achievements. Being First Lady doesn’t and should not mean reducing who you are! #PhDs”. Another shared: “Misogyny is when a man calls a woman with a doctorate ‘kiddo’; Misogyny is when the editor of @WSJ thinks a sexist attack is a good piece of journalism. Misogyny is following sexist tropes of the 50s. #DrJillBiden #DrBiden.” I pause, however, at the implication that Epstein’s misogyny is anachronistic. Misogyny, defined by Kate Manne as “a property of social environments in which girls and women are prone to face hostility because of the enforcement and policing of patriarchal norms and expectations,” is mobilized by the gendered norms and expectations of today. His piece cannot be reduced to fringe speak that reflects a bygone era. Rather, it is distinctive of a 21st century social order where women have yet to be elected to the world’s highest political office.

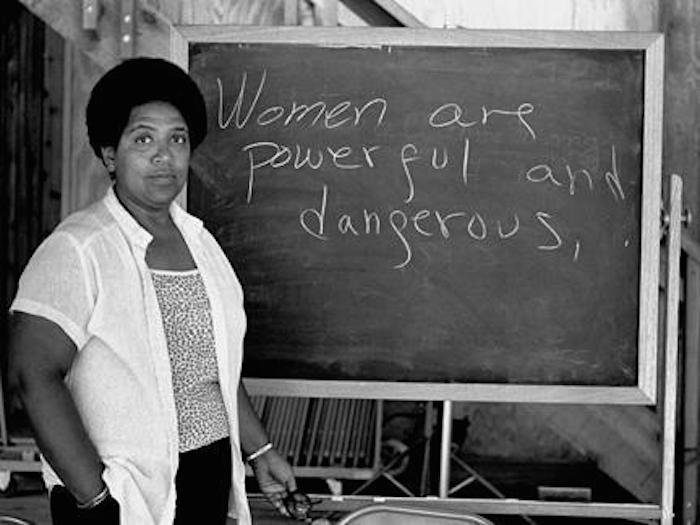

People like Mr. Epstein enact the violence of misogyny by policing how women take up space in a world made for men. Dr. Jill Biden ain’t it, he intones sagely. Sit down, be woman. And if you thought misogyny was the extent of Joseph Epstein’s appeal, try his misogynoir: “Political correctness has put paid to any true honor an honorary doctorate may once have possessed. If you are ever looking for a simile to denote rarity, try ‘rarer than a contemporary university honorary-degree list not containing an African-American woman.’” In stratifying categories of non-personhood, patriarchy has determined that Black women be relegated to the nadir. Honorary degrees, like white women with doctoral degrees, are already suspect, but disproportionately awarding them to African-American women, the most fraudulent kind of woman imaginable, is all the evidence you need of their worthlessness.

By Sarah-Anne Gresham

Sarah-Anne Gresham is an Antiguan Ph.D. student in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Rutgers University

(Image Credit: Mashable / Vicky Leta)