In the past 24 hours, overcrowding has made the news: “As France releases thousands, can Covid-19 end chronic prison overcrowding?” “Nine killed in Peru prison protest against overcrowded conditions during pandemic”. Earlier in the week, “COVID-19 Reaches Lebanon’s Overcrowded Palestinian Refugee Camps”. Overcrowding is the Janus face of the pandemic. On one hand, with the regime of social and physical distancing comes concern over overcrowding. Beaches and bars are dangerously overcrowded. When schools re-open, how will they maintain social distancing, how will they avoid overcrowding? In this context, overcrowding has a clear metric: six feet or two meters between each person. It’s measurable, there’s a formula. On the other hand, overcrowding is the `petri dish’ for infection: in prisons, jails, immigration detention centers, juvenile detention centers, in `overly dense’ neighborhoods and individual residences. Here, the math gets fuzzy, as do history and memory. Prisons have been overcrowded for as long as mass incarceration has been the ruling ideology; cities have been divided into “neighborhoods” and “slums”, the latter “relentlessly … overcrowded”, for as long as real estate and commodification of urban space have been a main economic driver. Why does it take a pandemic for `the world’ to take notice?

Consider these statements from the last couple days. In calling for Iran to release its female prisoners of conscience and political prisoners, UN human rights representatives noted, “Iran’s prisons have long-standing hygiene, overcrowding and healthcare problems.” In some places, prison overcrowding is not only long-standing but `notorious’: “Throughout Latin America, prisons are notoriously overcrowded, violent and dominated in large part by gangs or corrupt officials.” “The spreading specter of the new coronavirus is shaking Latin America’s notoriously overcrowded, unruly prisons, threatening to turn them into infernos.” “Throughout Latin America, prisons are notoriously overcrowded and violent, and Peru is no exception.” How did Latin American prisons become notoriously overcrowded while the equally overcrowded prisons of the United States are merely “overcrowded and underfunded” or “significantly overcrowded”. Prisons in the United States are described as having “a troubling history of overcrowding and unsanitary conditions”; prisons in France and Europe are described as a “combination of cramped quarters, poor sanitation and desperate overcrowding”.

Last year, the United Nations reported that by 2018, over 1 billion people were living in slums or informal settlements. In 2018, the world population was around 7.6 billion. 13% of the world was living in slums or informal settlements. 23.5% of urban populations were living in slums or informal settlements. Where was the `notoriety’ over the past thirty years of urban so-called development: escalating rents matched with reducing numbers of rental units, proportionately less and less “affordable and adequate housing”. For the urban poor, at first, and then for everyone but the urban rich, expulsion and exclusion became the daily in what was fast becoming a planet of slums.

Yesterday, when Cicero Public Health Director Susan Grazzini was asked about Cicero’s high rate of Covid-19 infection, her answer was short and direct: “It’s overcrowding. There are certain areas where we have more COVID-19 (cases). Its more places that are overcrowded.” A week or so earlier, when Gabriel Scally, the Royal Society of Medicine’s head of epidemiology, was asked about England’s urban high rate of Covid-19 infection, his answer was equally direct: “Houses in multiple occupation must be in the same category as care homes because of the sheer press of people. I have no doubt that these kinds of overcrowded conditions are tremendously potent in spreading the virus.”

This is our built environment. More segregated cities where increasing numbers of people live in lethally toxic overcrowded residences, overcrowded both in their respective residences and in their neighborhoods; where cities pay more to sequester the overcrowded than to attend to them. More prisons, more prisoners, where, again, overcrowded goes hand-in-glove with drastic, even criminal underfunding; where administrations, from national to municipal and county, pay more to sequester the overcrowded than to attend to them. This is a small part of the story of how we learned to stop worrying about overcrowding and love the apartheid bomb.

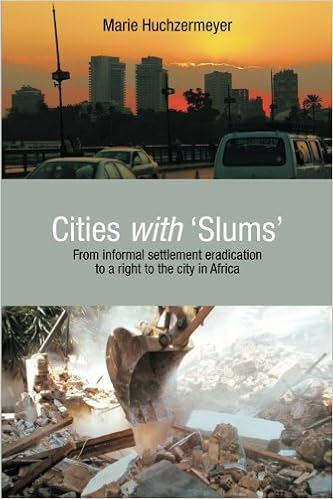

(Photo Credit: Meridith Kohut / New York Times)