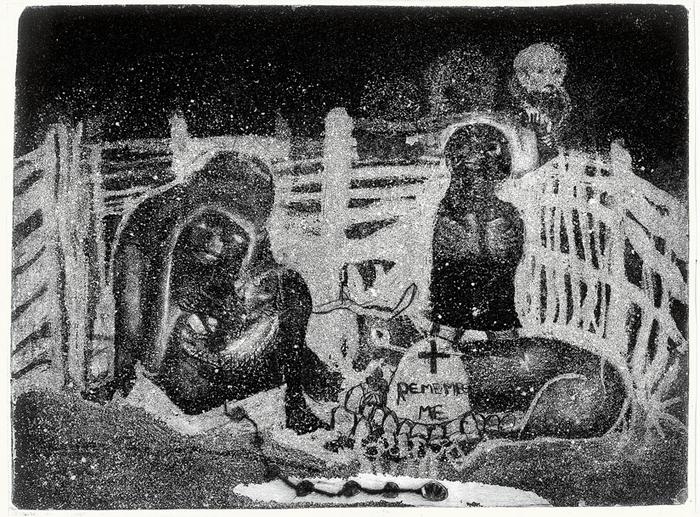

Hlelo Kana, a grade 4 learner at Samora Machel Primary School, won second place at the Philippi Arts Centre’s book quiz

Art is the way

Art is the way

is what they say

those bookworms

out Philippi Arts Centre way

(though art seems

only to matter

come vote-catching time)

Art is the way

where 40 or so

grade 3s and 4s

ace a book quiz

A book quiz

where they show

they can read

for meaning

(in isiXhosa)

Notwithstanding the ritual

of those PIRLS studies

that go the other way

What might the bookworms

have to say

“Book worms : Philippi learners ace Arts Centre book quiz“

(By David Kapp)

(Photo Credit: GroundUp / Qaqamba Falithenjwa)