Yesterday, December 25, hundreds of thousands of protesters, led and impelled by women and youth, took to the streets of Khartoum, demanding freedom, full democracy, a revolution. This was the tenth major demonstrations in the past two months. These protests have gone on, lled and impelled by women and youth, for the past thirty years, demanding full democracy, freedom, a revolution. Women and youth, leading, demanding, grasping freedom and justice: this is what democracy looks like. The government cut communications, blocked roads, fired tear gas, arrested scores, injured who knows how many.

In Sudan, on December 19, 2018, women took to the streets to protest a precipitous rise in bread prices. Those protests persisted and grew. As so often in food uprisings, the price of food was the visible spark that revealed an undergrowth of fire, and, as so often, women set and sustained the spark. Three years later, Sunday, December 19, 2021, women led protests of hundreds of thousands to commemorate the 2018 uprising, the spark they set, and to demand much more than a `return to civilian control’. Women in the streets of Khartoum and beyond demanded full rights, equality, freedom and justice for women, youth, everyone. They government responded with live bullets and sexual violence against women. According to numerous reports, security forces raped 13 women and girls that day. In the following days, women returned to the streets to demand justice. Actually, they had never left the streets.

Shaihinza Jamal explained, “We are here to put pressure so that this could stop happening. We will not allow such things ever to happen, and we can stop them.” Women protesters chanted, “They won’t break you! They won’t break us!” Jihan el-Tahrir, longtime Sudanese feminist activist, added, “Because women’s role in mobilising the Sudanese society is well-known, one approach long adopted by the regime has been breaking the society by breaking women.”

These are the daughters of a long line of Sudanese women demanding freedom and democracy. RememberJune 2012, when women students responded to astronomical increases in transportation and food prices? A few university women students took to the streets, shouting “Girifna!” “Enough is enough!” Within days, their small demonstration inspired a sandstorm, which was met with severe State repression. Remember the Sudanese women of June 2012? Remember September 2013, when, again in response to austerity measures this time involving gasoline prices, women took to the streets? Again, those protests turned into a national crisis, which, again, was met by severe repression. Remember the Sudanese women of September 2013, and the Sudanese Women’s Union of the 1950s and 1960s, and the Sudanese who have organized continually from the 1950s on, for women’s autonomy and national dignity? Well, they’re back, and they remember. They remember every detail of their history; they are the guardians of the revolution.

In a mass demonstration in late October, women carried signs reading, “Total civil disobedience. The decision of the people.” In a recent smaller, silent protest in Khartoum, Rayan Nour held a sign that declared, “The world is ruled by a woman who fights”. She explained, “My mom always taught me to not let anyone take my rights away from me and for me to get that by my hand if I had to and not wait for anyone to get it for me …. The first protest was called in the newspaper protest of the whores and the gays. And I was like, OK, whores, gays, let’s go.” Mothers, daughters, whores, gays, OK, let’s go. They’re back and they remember not only the past but the future. The world is ruled by women who fight.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

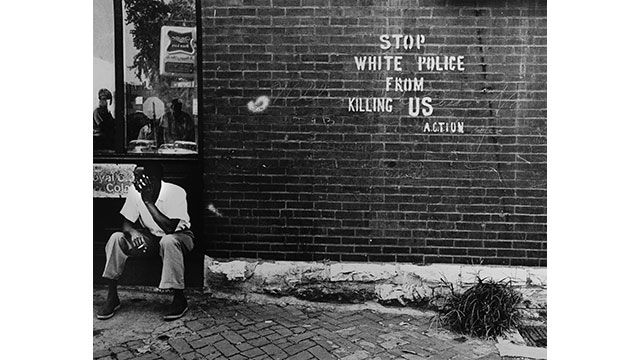

(Photo Credit 1: BBC) Photo Credit 2: New York Times / AP / Marwan Ali)