Twelve years ago, December 17, 2010, something happened in Tunisia: the Jasmine Revolution. Remember? On December 17, Mohammed Bouazizi, a street vendor, set himself on fire. It was a desperate act that lit the sky and the world. His act reflected a general sense of despair, and in that reflected despair, people saw transformative change as their only hope. Within 28 days, on January 11, 2011, President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali resigned. From its first flicker, the Jasmine Revolution was more than the ouster of a dictator. It was an assault on patriarchy that emerged from decades of women and youth organizing. Twelve years later, it still is, as this weekend’s parliamentary elections demonstrated.

Much happened immediately after Ben Ali’s resignation, including the formation of Ennadha, itself an outgrowth of the Movement of Islamic Tendency, formed in 1981. In the first post-Ben Ali elections, the Constituent Assembly election, Ennadha won a plurality of seats and so formed the new government. In 2019, jurist and law professor Kaïs Saïed ran for President, with Ennadha’s endorsement, and won. In 2021, demonstrations, led by youth and women, broke out across Tunisia, protesting police violence, corruption, economic conditions, and stringent COVID mandates. On July 25, 2021, Saïed suspended parliament and dismissed the Prime Minister, in what some have termed a “self-coup”. Then he engineered the removal of women from government and, largely, from the electoral process.

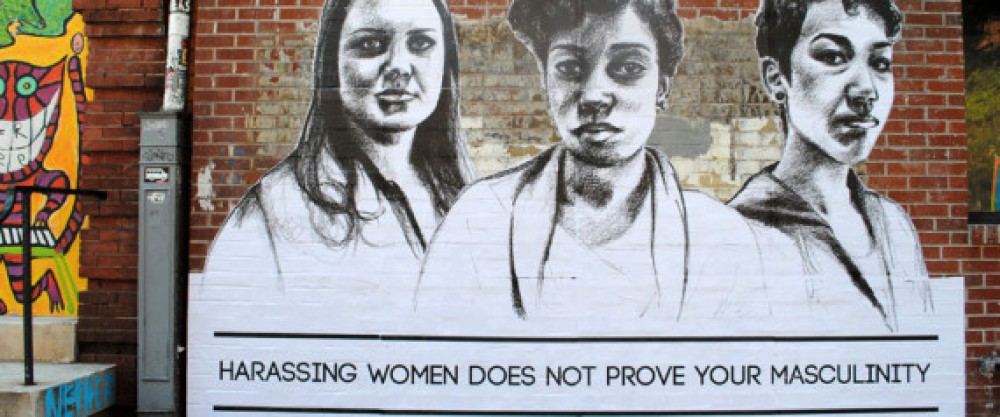

This was somewhat predicted by the years following the ouster of Ben Ali. For women, the first three years were “interesting”. The government seesawed repeatedly on its position vis-à-vis women’s rights, equality, and roles. The State and parts of Civil Society colluded in trying to diminish the significance of women’s work and contributions. Once the unity of the first phase of the Jasmine Revolution dissipated, fractures emerged. In the first three years, women reported increased attacks on women ostensibly for their attire. In some instances, women were attacked for not wearing a veil or for wearing jeans; in other instances, women were attacked for wearing veils. The policing of women’s bodies intensified until 2012, when a young woman was raped by police officers. When she took the officers to court, she was charged with public indecency. Across much of Tunisia, women and men shouted, “We are not going back!”

In January 2018, women led protests against the IMF imposed austerity budget that went into effect January 1, 2018. Their rallying cry was: “Fech Nestannew?” “What are we waiting for?” “Qu’attendons-nous?” “فاش نستناو ؟”. The IMF budget consisted, once again, of increased taxes, sliced subsidies, subjecting the civil service to “efficiencies”, raising food prices, ending recruiting and hiring for public sector jobs. Women responded: “When do we get the jobs we struggled for and were promised? When will food become generally affordable? Where is our housing? What are we waiting for? Travail, pain, liberté et dignité! Employment, bread, liberty, and dignity!”. The women invoked the memory of the 1984 Intifada al-Khubez, the Bread Uprising.

On March 11, 2018, women in Tunisia marched in an historic first, a march for women’s equality in inheritance rights, a first-ever demand not only for Tunisia but for the Arab world. In Tunisia, equality is a right, not a favor. They chanted, “Moitié, moitié ; c’est la pleine citoyenneté!”; “Pour garantir nos droits, il faut changer la loi!”; “L’égalité est un droit, pas une faveur!”. “50-50 equals full citizenship!” “To guarantee our rights, we have to change the law!” “Equality is a right, not a favor!”

And that brings us to this weekend’s parliamentary election. In the months leading up to the election, Saïed and his allies engineered a new electoral law which effectively removed women from running for office, this in a country that had decades of gender parity legislation and practice. Of the 1427 candidates, 214 were women, 14.99%. That’s gender parity under the new regime. Many, rightly, predicted the result would be either a male-dominated or all male parliament. This in a country in which “a supermajority (84.5%) thought that women should be allowed to participate in politics.”

Everything seemed ready for Kaïs Saïed’s ascendancy to complete autocratic control. With the elimination of women, the elections seemed a foregone conclusion. But those who bought that line hadn’t considered the histories of women and youth organizing in Tunisia, what one writer called “L’éloquence des chiffres: Le pouvoir lâché par les jeunes et les femmes” The eloquence of numbers: the power unleashed by youth and women. “Unleashed” as in erupting, exploding. Fewer than 9% of the electorate showed up to vote. Don’t want us at your party? Fine. We’ll go somewhere else. 9 million people are registered voters. 800,000 voted. Of the 800,000, 34% were identified as women, 66% as men. More importantly, 8,200,000 said “What are we waiting for? Not this!” Now many are calling for Kaïs Saïed’s resignation. Whether that happens or not, this weekend’s election was another chapter in the long revolutionary history of Tunisian women and youth organizing, pushing back, pushing forward.

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Photo Credit: Tunisie Numérique)