The national campaign for the legalization of cannabis has gained momentum in the past two years with the introduction of bills in Congress such as the MORE Act and the PREPARE Act. Yet, more movement has been taking place on the state level; 21 states have fully legalized recreational cannabis sales, and 18 states have legalized medicinal sales. Early adopters of recreational cannabis, for example, Colorado have been able to make hundreds of millions of dollars a year from recreational cannabis sales from sales tax alone.

While it seems like some progression against prohibition is taking place, the story becomes more complicated when using a gendered lens. Historically, men of color, particularly Black, Indigenous, and Latino men, have been overrepresented in the US’s prison population for drug-related crimes, despite somewhat equal substance use rates across racial groups. Since the Nixon and Reagan Eras of prohibition, men of color have also been more likely to be arrested and imprisoned for drug-related crimes than their female counterparts.

However, this imbalance is starting to change in the 21st century. Despite the push for de-carceration in the past 20 years, women’s prison populations have increased. Between 2000 and 2019, drug arrests for women in the US increased by 56.2%, while drug arrests for men have gone down by 0.01%. Similarly, incarceration rates differ by race; Black women are about 200% more likely and Latinas are 20% more likely to be incarcerated than white women. Native American women are incarcerated at six times the rate of white women.

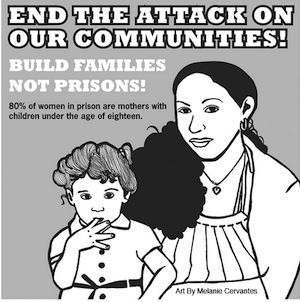

The racialization and gendering of the War on Drugs is especially apparent when talking about mothers. About 60% of women in state and federal prisons are mothers to children under the age of 18, with many of these women being sole caregivers. The sheer cost of incarcerating a woman for one year can be upwards of $100,000 in states like California. This does not take into account the billions of dollars spent across the country to construct new prisons, nor does it account for the social cost of separating families. These social costs include the effect of the parent’s incarceration on their children and on those who become their subsequent guardians. Due to the disproportionate representation of women of color in our prison system, these costs are borne primarily by Black, Latina, and Indigenous women, further deepening an already existent gap in inequality, opportunity, and net worth.

The fight for legalization is not just a personal freedom issue: it is an equity issue. States like New York have taken special care to make sure that dispensary licenses are awarded to people who have been negatively impacted by the War on Drugs, namely Black and Latino men.

While cannabis equity laws are necessary to prevent a venture-capital takeover of an industry in its infancy, it has unintentionally ignored the struggles of women. In the first round of applications for dispensary licensure, only 7% of license awardees were women. New York State’s system first prioritizes those who have had an arrest of their own, and then subsequently prioritizes those who have had a family member arrested. “I understand that the person who actually went through [the arrest and conviction] should be awarded more points,” said license applicant Venus Rodriguez to Politico. “But what’s that scale? And how do we measure suffering? We’ve all suffered.”

It is likely nearly impossible to quantify the harmful impacts of the War on Drugs, beyond simple arrest and conviction numbers. However, it is undeniable that women are not only the fastest-growing prison population group in general but also represent an increasing number of drug arrests and convictions.

As more and more states have legalized cannabis sales, women’s involvement in the industry is actually decreasing. In 2019, 36.8% of cannabis executives were women, yet that number dropped to 22.1% in 2021. For reference, the national average percentage of executive roles filled by women is 29.8%. The number of minority executives in the cannabis industry also decreased, from 28% in 2019 to 13.1% in 2021. Licensure cannot be the only measure of equity in the cannabis industry for women and women of color; we need concerted efforts to ensure that women do not face additional gaps in opportunity in the legalization movement.

The racial facet of the War on Drugs still continues, despite the country’s effort to pass more sensible drug legislation. Thus, on top of existing equity movements such as dispensary licensure, it is imperative that women of color, in particular Black women, are centered in the narrative of equity moving forward. In redressing the wrongs of Nixon and Reagan-era policies, we must also keep an eye on current trends in the enforcement of drug prohibition in order to prevent a new generation of women behind bars.

(By Laura Goodfield)

(Image Credit: Maya Chastain / healthline)