January 2015: “On Thursday, the United Kingdom’s Ministry of Justice issued its Safety in custody quarterly update to September 2014. The report is grim.” September 2018: “In July, the Chief Inspector of Prisons for England and Wales released their annual report, and it was predictably grim, especially for women prisoners.” February 2021: On Thursday, January 28, the United Kingdom’s Ministry of Justice issued its Safety in Custody Statistics, England and Wales: Deaths in Prison Custody to December 2020 Assaults and Self-harm to September 2020. The report is generally grim, and especially so for women.” February 2022: “Once upon a time, the word custody meant protection, safekeeping, responsibility for protecting or taking care of. No longer. If one is to take the sorry and sordid output and history of the United Kingdom’s Ministry of Justice, custody today means the power to cage and code for cruelty. It’s that time of the year again when the Ministry releases its in no way long awaited “safety in custody” reports, and, yet again, one can only look at the numbers and wonder. If this is safety in custody, what would danger look like?” Well, here we are, September 2023, and the United Kingdom Ministry of Justice has release yet another `grim’ Safety in Custody Statistics, England and Wales: Deaths in Prison Custody to June 2023 Assaults and Self-harm to March 2023, and this one is actually worse than its predecessors, and, like its predecessors, will go largely unread, undiscussed, and without response, in word or deed. So … here it is, and here we are.

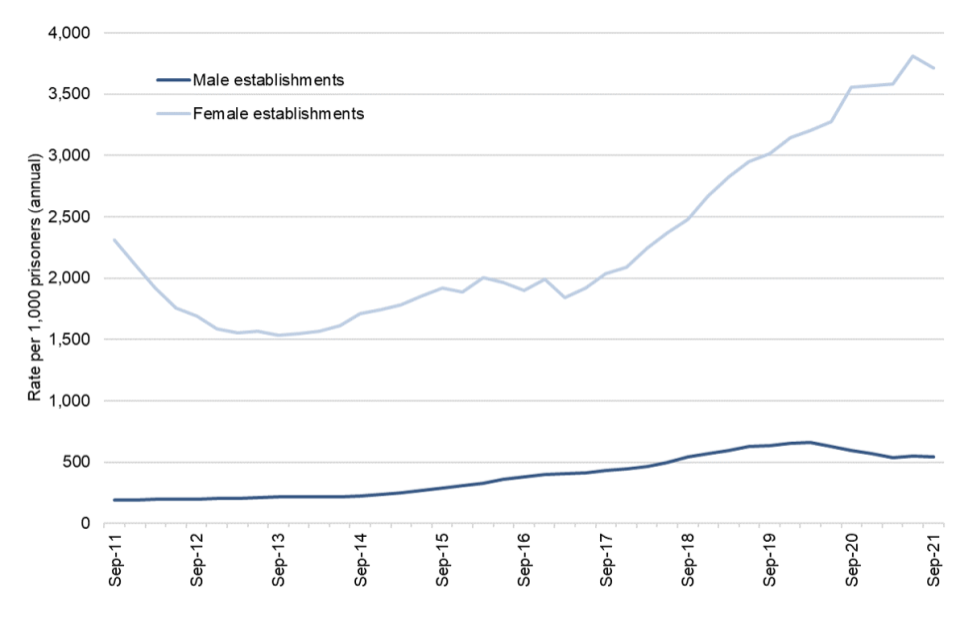

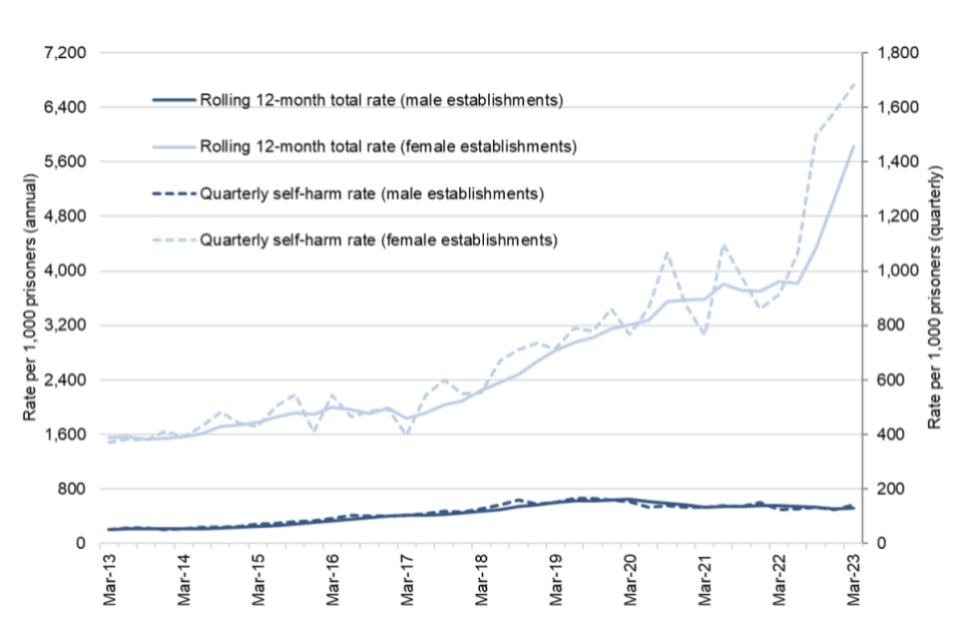

“There were 59,722 self-harm incidents in the 12 months to March 2023, up 11% from the previous 12 months, comprising of a 1% decrease in male establishments and a 52% increase in female establishments. Over the same period, the rate of self-harm incidents per 1,000 prisoners, which takes account of the increase in the prison population between this and the previous year, decreased 5% in male establishments but increased 51% in female establishments.”

Here are the Statistician’s comment: “In female establishments, both self-harm and assault incidents increased, by 52% and 16% respectively, with self-harm incidents reaching their highest level in the time series …. The rate in female establishments has increased considerably by 51% to a new peak (5,826 per 1,000 prisoners), whereas it has decreased 5% in male establishments (523 per 1,000 prisoners), meaning the rate is now more than eleven times higher in female establishments. This was driven by a substantial increase in the average number of incidents among those who self-harmed in female establishments, from 11.1 to 17.0, a much larger increase than previously despite this continuing an increasing trend seen for the last six years.”

The comments continue, more or less in the same vein, but you get the picture. The trend of self-harm among incarcerated women has been bad and getting worse for the past six years, but this year, the increase was much larger. Again, no one other than the usual suspects will pay any attention to this report. How do we know? Because the report was released end of July, and it’s already mid-September, and the response has been a resounding silence. Actually, more like a blurry noise, always there but not worth noticing or discussing.

The violence against women perpetrated by the State is increasing. The report notes that the assaults by women are less violent than those of men. What does that tell you? That the women are sending a message by carving into their own flesh, again and again and again, and all they get, in response, is another government report from a ministry that dares to use the name “Justice”. In circumstances like this, language only exists to demonstrate its own vacuity, our own capacity to empty words of any real significance: grim, custody, justice, harm, responsibility, care, prison, women. We study, we write, we organize … and the violence does more than continue, it escalates: “The number of incidents and rate of self-harm in the female estate are now at the highest level in the time series.” Who cares?

(By Dan Moshenberg)

(Infographic: UK Ministry of Justice)

Yesterday, England’s House of Commons Justice Committee delivered its report, “

Yesterday, England’s House of Commons Justice Committee delivered its report, “