One night in 2010 CN’s* husband hit her so hard that she lost consciousness. CN was taken to the hospital, where she spent the night. The day after she was discharged, she decided to lay criminal charges against her husband. And this is where CN’s story stops making sense. Within 24 hours of approaching the police for assistance, CN was herself arrested, detained and assaulted by the police.

First, CN was given the wrong advice by police officers on duty, and told that she needed a domestic violence protection order from a magistrates court before she could lay a criminal charge. The court simply sent her back. The inspector assigned to the assist CN asked her for her telephone numbers, which he then used to call her husband, to invite him to the charge office. When CN’s husband arrived the inspector first spoke to him alone, and then told CN that she must discuss the matter with her husband to see if they could resolve it. When CN reported to the inspector that their discussion had not resolved the issue, and that she wanted to proceed with a charge, the inspector discouraged her. He told her that her husband would similarly lay a charge against her “for slapping”, and if this were to happen she would also be liable to be arrested. The inspector then asked them to write down their statements, and once they had done so, the inspector arrested both CN and her husband. They were both charged and detained in separate police cells at the police station, where CN then stayed the night.

The following morning, another police officer came to CN’s cell and informed her that he had come to take her to court. As she was being escorted to a police van she asked the officer to allow her a moment in order to speak to a more senior officer. But the officer sternly ordered her to board the police van, and then forcibly flung her into the back of the police van.

CN was subjected to “a dreadful series of traumatic, humiliating, dehumanising and flagrant violations of her rights to dignity, freedom of the person and bodily integrity.” This series of events makes so little sense because it is almost the polar opposite to what the South African legal framework envisages for domestic violence cases.

The Domestic Violence Act of 1998, a well-known piece of legislation that has been on South Africa’s law books for almost 17 years, is very clear about the responsibility of police officers in South Africa. In fact, the legislature regards domestic violence so seriously, that any failure to comply with one’s police duties in terms of the Act constitutes misconduct for the purposes of disciplinary action. The Regulations to the Act go into further detail about the duties of police officers, and a National Instruction issued to all police officers in 1999 leaves nothing open to interpretation. South Africa also has a Victim’s Charter, implementation audit tools, and a host of cooperative structures at local, provincial and national level where domestic violence can be discussed.

And despite all this legal regulation, the South African Police Service has been coughing up a lot lately in civil court for not doing their job. While there are pockets of excellence within the South African Police Service, it is an open and disgraceful secret that our police, particularly in townships and far-flung poor areas, perform badly when it comes to assisting victims of domestic violence. Police officers’ treatment of victims at station level often causes secondary trauma: a refusal or inability to come when called, a failure to explain a victims’ rights and legal options, sending victims home to deal with it “in the family”, and a failure to even understand their own duties under the Domestic Violence Act, or to even have a copy of the Act readily available in their stations. We know this first-hand from women seeking help, we know this scientifically from research, and we even know it from the police themselves. And we have known it for a long time.

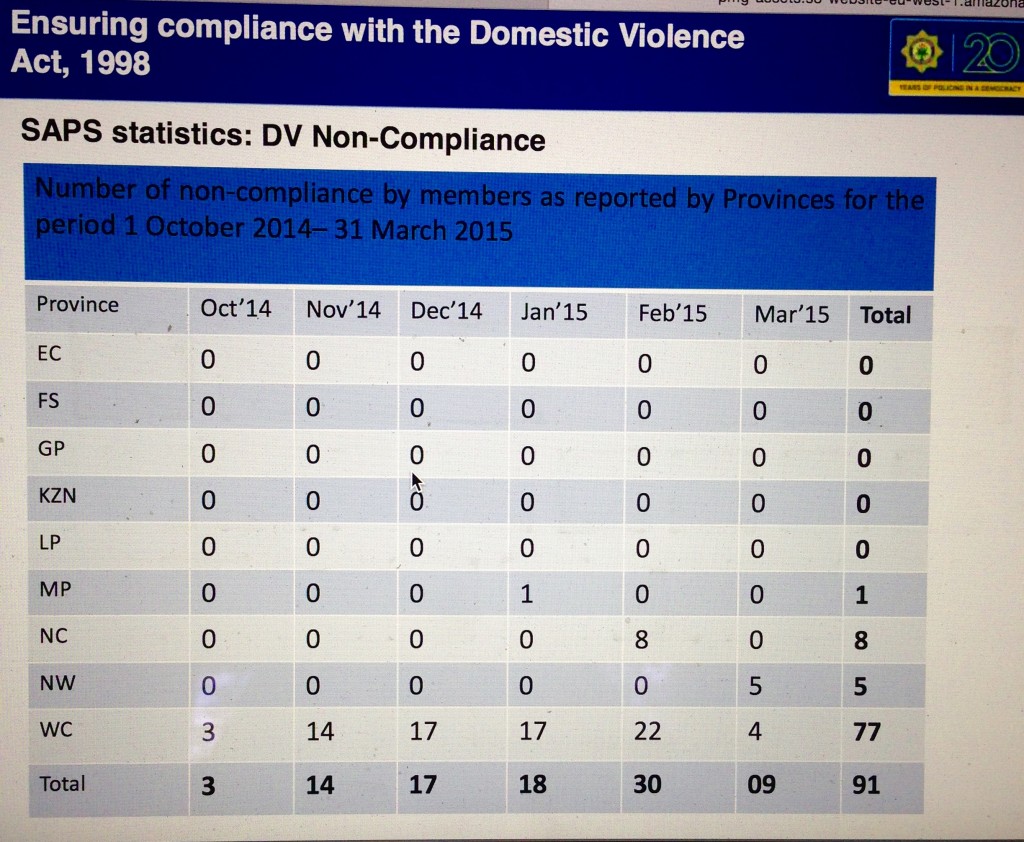

What is most concerning is not that our police are doing badly, but that there is no desire to be honest with themselves and the public about shortcomings, and no real commitment to improving the situation. In a briefing to the parliamentary Portfolio Committee of Police, the SAPS would have us believe that they are doing well, and that almost no officers failed to comply with the Domestic Violence Act between 1 October 2014 and 31 March 2015.

Excerpt from presentation by the South African Police Service to Parliamentary Portfolio Committee for Police, on 18 August 2015.

They also reported that 100% of all 1 140 South African police stations were rendering “victim-friendly” services at the end of the first quarter of the 2015/16 financial year.

Which begs the question, why does the Women’s Legal Centre and other organisations continually deal with complaints, such as a recent case where a client, whose husband brandished and threatened her with a firearm on several occasions, had to approach three different police stations in her area before she could obtain police assistance? Why are there continued civil claims for damages against the police, for failing victims of domestic violence? Why is the Civilian Secretariat for Police reporting that only 1 of the 156 police stations audited in 2014 were fully compliant with the Domestic Violence Act? Why is it that women who are in possession of domestic violence protection orders, are still being abused and even killed by their partners?

There is no scarcity of recommendations for the police on improving their response to domestic violence, and thereby often preventing it. Civil society has, since the operationalisation of the Act, produced a multitude of research papers. Interest groups lobby relentlessly and women’s and men’s organisations clamour to be heard on the issue by various branches of government. We express the same concerns, and make the same arguments and appeals year in, and year out. In fact, even to those of us in the gender-based violence sector, we are starting to sound like broken records. In 2014, the Khayelitsha Commission of Inquiry heard extensive evidence about the handling of domestic violence cases by police. Community members testified about their experiences, the police released an unprecedented amount of internal data and documentation, and this in turn was analysed by various experts. The police themselves cooperated with the Commission, after initially refusing to take part, and ended up testifying frankly about their own challenges. And yet, the evidence-based recommendations (see Recommendation 14) which have national applicability have been rejected by the national Police Commissioner.

Police officers in South Africa can and must prevent domestic violence, through a quality response to victims. But there is complacency about ongoing police failure in this regard that seems to have set in, and it cannot be fixed by throwing more law or policy at it. Nor do civil claims seem to be driving home the message that the status quo is unacceptable.

The fact is that one station commander who cares about his station responding quickly and effectively to domestic violence, and takes responsibility for making it so, can do more good than ten policy documents and 20 reports to parliament. This is accountability. We should no longer be asking, “what must be done” but rather, “who is doing it”. Accountability means taking responsibility for what must be done, and it means real, personal consequences for failure to do your job.

(Image credit: Heinrich Böll Southern Africa)